New Jersey Future Blog

Is Redevelopment the ‘New Normal?’

January 28th, 2014 by Tim Evans

The End of Sprawl?

Did the 2008 recession really rewrite the development playbook? Are demographics really destiny (pdf)? Commentators of many stripes have recently been declaring that the age of suburbanization is at an end, and that the future of land development is going to look a lot like the past, with people returning in droves to in-town living. Now, some of their prognostications are actually starting to show up in data. Our two-part series takes a look at some of the sorts of data patterns that one would expect to see if we really were standing at the threshold of a new era of redevelopment. Part I of a two-part series.

The most recent county and municipal population estimates in New Jersey (for 2012) suggest that the growing popularity of redevelopment shows no sign of abating, and may be accelerating. Indeed, older, built-out places seem to be weathering the lingering effects of the recession much better than the formerly high-flying outer-suburban counties.

The most recent county and municipal population estimates in New Jersey (for 2012) suggest that the growing popularity of redevelopment shows no sign of abating, and may be accelerating. Indeed, older, built-out places seem to be weathering the lingering effects of the recession much better than the formerly high-flying outer-suburban counties.

Redevelopment Trend Started

More Than a Decade Ago

The trend toward redevelopment – the accommodation of new population and employment growth in places where infrastructure is already in place, through the reuse of previously developed land and buildings – has been underway in New Jersey for a while now, as befits the state that has developed more of its land than any other state in the nation and is hence running out of new places to put things. As documented by New Jersey Future in our December 2010 report Built Out but Still Growing, a 1998 revision to the building code for rehabilitating existing buildings did a lot to get the ball rolling, opening the door for a new round of growth in many already-built municipalities. As the report noted, the 204 municipalities that were already at least 90 percent built-out as of 2002 together issued 2.7 times more building permits in the 2000s than they had in the 1990s and more than doubled their combined share of total statewide building permits issued, from 15.1 percent in the 1990s to 33.6 percent in the 2000s.

The rise of redevelopment as a new paradigm was brought into sharper focus when the recession and housing market crash of 2008 rewrote the calculus that underlies households’ implicit tradeoffs between housing costs and commuting/transportation costs. Under the old suburban/exurban model, people in search of cheaper housing would flee to the suburban fringe, where developable land was still plentiful and new homes were relatively less expensive. The price they paid for cheaper housing was a longer commute and longer travel distances to other daily activities. In other words, they swapped housing costs for transportation costs.

But the one-two punch of a spike in gas prices and the collapse of the housing bubble in 2008 seems to have prompted a reassessment of the “drive ‘til you qualify” strategy. Suddenly, an existing home on a smaller lot in a closer-in small town or older suburb looked like it might be a better deal, once all costs are factored in. Plus, these short-term shocks were superimposed on the longer-term phenomenon of Millennials’ questioning the wisdom of the whole low-density suburban experiment in which New Jersey – and the nation – has been engaged since the 1950s. The Millennial generation – now into its prime household-formation years – has been expressing a preference for city living and more urban amenities (like proximity to public transportation) and eschewing homeownership, especially the kinds of houses they grew up in. They also want to drive less, with vehicle miles traveled per capita by 16-to-34-year-olds falling by 23 percent between 2001 and 2009.

New Data: This Could Be the New Normal

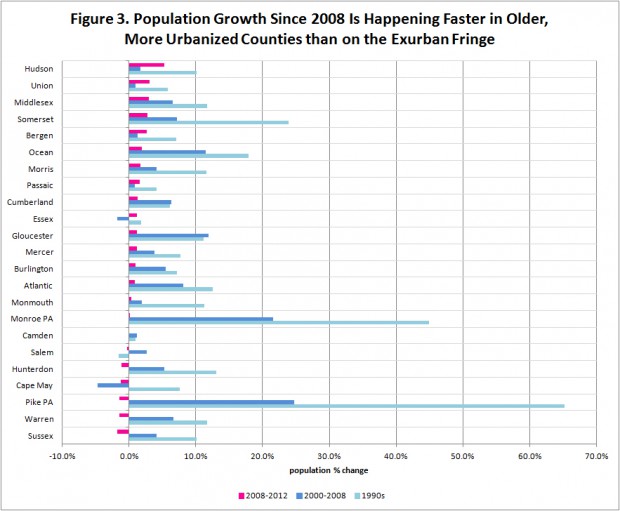

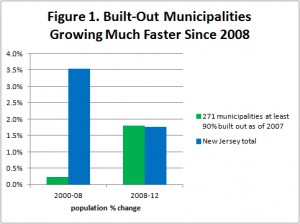

The combined effects of all of these trends, both short-term and long-term, can be seen in the dramatic changes in population growth patterns that have taken place since 2008. There are 271 municipalities that were at least 90 percent built out as of 2007 – that is, they had already developed at least 90 percent of their total buildable acreage. As a group, these municipalities grew by only 0.2 percent between 2000 and 2008, accounting for only 3.6 percent of total statewide population growth, but then turned around and accounted for 54.5 percent of the state’s total population growth from 2008 to 2012. (See Figures 1 and 2.) The older cities and boroughs falling in this group of 271 include such places as Garfield, Hackensack, Belleville, Bloomfield, Montclair, Bayonne, Weehawken, Clifton, Passaic, Cranford, Linden, and Plainfield. Many of these places had been stagnant or even losing population for decades before experiencing their revivals in the later part of the 2000s.

The combined effects of all of these trends, both short-term and long-term, can be seen in the dramatic changes in population growth patterns that have taken place since 2008. There are 271 municipalities that were at least 90 percent built out as of 2007 – that is, they had already developed at least 90 percent of their total buildable acreage. As a group, these municipalities grew by only 0.2 percent between 2000 and 2008, accounting for only 3.6 percent of total statewide population growth, but then turned around and accounted for 54.5 percent of the state’s total population growth from 2008 to 2012. (See Figures 1 and 2.) The older cities and boroughs falling in this group of 271 include such places as Garfield, Hackensack, Belleville, Bloomfield, Montclair, Bayonne, Weehawken, Clifton, Passaic, Cranford, Linden, and Plainfield. Many of these places had been stagnant or even losing population for decades before experiencing their revivals in the later part of the 2000s.

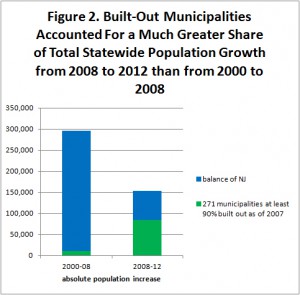

The trend is evident at the county level as well. The top five fastest-growing counties in New Jersey from 2000 to 2008 were Gloucester, Ocean, Atlantic, Somerset, and Warren, mainly a continuation of the dominant pattern of the previous five decades, with most new growth happening at the edges of the New York and Philadelphia metropolitan areas. But from 2008 to 2012, the top-five list looks decidedly more urbanized, with Hudson and Union counties (the two most developed counties in the state) claiming the top two spots and older-suburban Middlesex and Bergen also making the list. The other two North Jersey “urban core” counties – Essex and Passaic – now appear in the top 10, after being two of the three slowest-growing counties from 2000 to 2008. (See Figure 3.)

On the other end of the density spectrum, the wind has suddenly gone out of the sails of many exurban counties. Hunterdon and Warren counties – both of which were among the top five fastest-growing New Jersey counties in the 1990s, and both of which were still in the top 10 for 2000-2008 – have actually experienced small declines in population since 2008, as has neighboring Sussex County. Even more remarkable is the dramatic reversal in Pike and Monroe counties in northeastern Pennsylvania. Those counties were two of the three fastest-growing counties in the entire northeastern United States in the 1990s and in the early 2000s, thanks largely to out-migration from northern New Jersey and New York City. But Monroe’s growth slowed to a paltry 0.13 percent between 2008 and 2012 (compared to statewide rates of 1.6 percent in Pennsylvania and 1.8 percent in New Jersey) after growing by 21.6 percent from 2000 to 2008 (and by 44.9 percent in the 1990s), and Pike transitioned from 65.6 percent growth in the 1990s and 24.7 percent growth between 2000 and 2008 to an actual population loss of 1.5 percent from 2008 to 2012. (Looking just at the last two years, Monroe County’s meager growth has further deteriorated into a loss as well.)

While it may be a bit premature to proclaim the end of sprawl, evidence is certainly mounting that a new era of redevelopment is at hand.

Learn more about redevelopment strategies and opportunities at New Jersey Future’s upcoming Redevelopment Forum March 14.