New Jersey Future Blog

New Jersey Lags Behind in Some Key Real Estate Trends

December 12th, 2014 by Elaine Clisham

A new report from the Urban Land Institute and PricewaterhouseCoopers outlines several key emerging trends real-estate investors should look for in 2015. A review of the first chapter shows New Jersey is well positioned to capitalize on some of these trends, and modest fixes will help it catch up to others. But some of New Jersey’s deficiencies — transportation and water infrastructure in particular — will take significant investments to fix, and if we don’t fix them, we put ourselves at an ever-greater competitive disadvantage.

A new report from the Urban Land Institute and PricewaterhouseCoopers outlines several key emerging trends real-estate investors should look for in 2015. A review of the first chapter shows New Jersey is well positioned to capitalize on some of these trends, and modest fixes will help it catch up to others. But some of New Jersey’s deficiencies — transportation and water infrastructure in particular — will take significant investments to fix, and if we don’t fix them, we put ourselves at an ever-greater competitive disadvantage.

Here are some of the trends real-estate investors are looking at, according to the report:

- The 18-hour city. Not all cities can be “the city that never sleeps,” but many smaller metros are focusing on making sure housing, employment and entertainment are all within easy reach of each other. The growing number of such places gives investors greater locational choice, which means the city that closes up shop at 5 pm when its workers go home is increasingly at a competitive disadvantage.

- Technology is an indicator. “The densest social-networking markets are also the densest physical markets for real estate” is one of a line of clear indicators cited by the report that the rise in technology has not meant a corresponding drop in the importance of proximity. Place still matters.

- Demand for new housing will increase. Even despite the recession, growth in new-household creation has continued, benefiting particularly the rental construction market (see below), at the expense of large single-family home construction.

- Renting by choice. Both Millennials and Boomers are finding renting an attractive option, for a variety of reasons ranging from affordability (the report notes that disposable income growth has been lagging behind housing sales price growth) and lack of a nest egg to a desire to be free of home maintenance and upkeep to fear of another housing-market collapse. Places that offer a range of housing choices, in particular more rentals of smaller size, are in a better position to capture these two growing segments of the real estate market. And areas that reduce housing costs by increasing supply and variety will also better be able to accommodate Boomers’ desire to age near their children.

- Jobs will chase people. In particular, the report highlights a nationwide shortage of knowledge workers. Since job growth is a key factor for filling office space and new housing, the areas that are able to offer the kind of environment that can attract and keep knowledge workers will be the areas in which employers seek to locate.

Industrial has a future. Manufacturing reshoring, increased homebuilding, the change in retailing business models, and “the need for logistics firms to focus on ‘last-mile’ issues” all mean manufacturing has a future in smaller markets. - The suburbs aren’t dead. Suburban markets with two key characteristics — enough density to foster live/work/play environments, plus transit and walkability — are rapidly learning from their urban neighbors and transforming themselves into smaller versions of the 18-hour city. In particular, the report cites “traditional ‘railroad suburbs'” as being well poised to capitalize on their good bones, but also mentions re-imagined shopping malls, both strip and traditional.

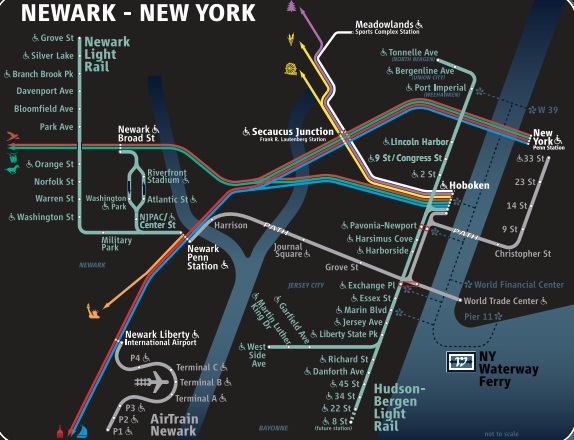

- Get serious about infrastructure. As the report points out, “The Millennial generation is intolerant of congestion and delay — on highways and in transit.” Businesses depend on talent and customers, and they “‘solve back’ to the real estate from that.” Economic growth is projected to slow in areas that do not invest in infrastructure, and, while infill redevelopment is a key opportunity in many markets, it is a lot less attractive when the underlying infrastructure is aging and underfunded.

- Plain vanilla and sprawl are out. That includes highway-dependent office parks; properties with excessive parking; properties tied to an assumption of growth in tract housing, particularly at the outer edge of a metro area; and property with no appeal to Millennials or Boomers.

New Jersey is well positioned to take advantage of some of these trends, but is lagging behind some others. Many municipalities could increase the variety of housing choices they offer by reviewing how restrictive their residential zoning is, and allowing, where appropriate, more multi-family construction, particularly of smaller-size units. The state also has its share of “railroad suburbs,” such as Somerville and Fanwood, that are already capitalizing on their transit asset.

However, we also have our share of vanilla-sprawl assets — properties such as suburban office parks and distressed malls — that present a significant redevelopment challenge. And we don’t have the world-class infrastructure that we need, either for transportation or, in our urban areas, for water, and our historic lack of investment in upkeep and upgrade of these assets has now put us behind. We need a concerted effort to address these two key trends ambitiously, or we will not regain our competitive advantage.