New Jersey Future Blog

Report Gives New Jersey High Marks for Designating Opportunity Zones in Smart-Growth Locations

January 9th, 2019 by Tim Evans

However, communities should guard against possibility of displacing existing residents

The Opportunity Zones program, announced earlier this year, is a new federal program enacted as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that is designed to attract capital investment into long-neglected neighborhoods characterized by disinvestment and concentration of poverty, by giving preferential tax treatment to funds that invest in projects in such areas. Each state was tasked with choosing its own set of census tracts to be designated as Opportunity Zones, subject to certain income criteria. The Department of Community Affairs administers the program in New Jersey and was responsible for selecting New Jersey’s Opportunity Zone tracts.

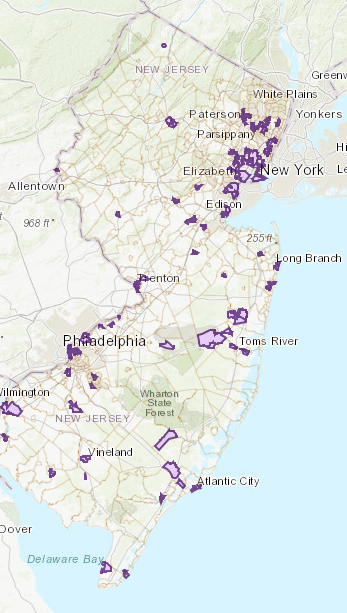

The national smart-growth group LOCUS has now released its National Opportunity Zones Ranking Report, which profiles the full set of census tracts nationwide – all 7,824 of them (there are 169 in New Jersey) – that were selected as Opportunity Zones (OZs) by their host states.

The report ranks the OZs on two composite indices: the tract’s “smart growth potential” (a combination of rankings on “walkability, job density, housing diversity, and distance to the nearest Top 100 central business district”), and its “social equity and vulnerability” (a combination of rankings on transit accessibility, housing and transportation affordability, diversity of housing tenure, and the “Social Vulnerability Index,” which is itself an index of 15 socioeconomic variables, developed by the Centers for Disease Control). The second metric is intended to gauge the risk that new development in a tract will result in displacement of existing residents with lower incomes.

The report’s press release caught the attention of several media outlets (NJ Spotlight, ROI-NJ) because it singled out an OZ tract in Newark that scored high on both indices. More generally, though, the report gives New Jersey good marks for its selected tracts compared to the rest of the country. While the report indicates that “the majority of the designated Opportunity Zones could be described as low density, drivable suburban areas with significantly higher housing and transportation costs, higher greenhouse emissions and lower quality of life,” it cites New Jersey as being among the top six states (along with New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio, and California) with the most high-scoring OZs in terms of smart growth potential. (The full report does not provide data on all OZs, so it is not possible to quantify how well New Jersey’s 169 OZs score as a group compared to the rest of the country.)

This observation is consistent with what New Jersey Future’s own analysis already pointed out when the list of OZs was first released, using our own smart-growth metrics:

An even more substantial majority of the Opportunity Zone tracts – 127 out of 169 – are located in municipalities that score well on all three of New Jersey Future’s metrics of compactness and walkability: population and employment density, presence of a mixed-use downtown, and local street network density. And even among the exceptions, many are located in parts of their host municipalities that possess the raw materials – assets like transit proximity and an existing grid street network with sidewalks – for becoming more “center”-like, and hence may show a quick return on investment. Being located in a walkable, mixed-use neighborhood is a promising indicator, given that much of the state’s recent population growth has been happening in such places, thanks in large part to the pronounced preference of the Millennial generation for a “live-work-play” environment.

and:

A healthy majority – 108 out of 169 – of the tracts selected as Opportunity Zones are within half a mile of one of the state’s 244 transit stations (including major bus terminals). Transit proximity offers access to a larger number of jobs, and has recently regained importance as a driver of population growth, as New Jersey Future has highlighted.

The LOCUS report suggest s that New Jersey does indeed stand out from most other states in its concern for steering much-needed investment specifically into underserved neighborhoods that are also compact, walkable, and offer access to public transit.

At the same time, the report provides a good reminder that steering capital into places that are showing at least some nascent signs of revitalization has the potential to lead quickly to long-time residents getting displaced if steps aren’t taken to protect them. It cautions, “History has repeatedly demonstrated that investment without protective equitable policy and process mechanisms leads to gentrification, displacement, and a lack of access to benefits in many low-income and communities of color.” The OZ in downtown Newark that attracted media attention is a prime example: It scored in the top 10 nationally on smart growth potential, but also scored in the top 10 for social vulnerability, meaning that existing residents (particularly renters) are vulnerable to being displaced if trends continue.

Fortunately, Newark is looking ahead and taking steps to ward off the possibility that burgeoning commercial and high-end residential growth in its downtown area could end up crowding out long-time residents and excluding non-wealthy newcomers from moving in. Last year it passed an inclusionary zoning ordinance that calls for 20 percent of the units in any development of 30 units or more to be affordable to low- and moderate-income households. This will ensure that new development remains accessible to households across the income spectrum that may be seeking to relocate to Newark, while also reducing development pressure on neighborhoods with existing populations of lower-income households. The 74 other New Jersey municipalities that host at least one OZ tract – ranging in size from Jersey City (2017 population = 270,753, where an inclusionary zoning ordinance is currently under consideration) to Sussex Borough (population = 2,024) – should be considering similar strategies. (Technically, there are two other, even smaller, municipalities that fall into this group: West Wildwood, population 566, and Teterboro, population 69. But these municipalities are so small that they are entirely contained within census tracts that also contain part or all of another municipality — Wildwood and South Hackensack, respectively. Still, these small municipalities should be taking the same steps as their larger neighbors to ensure that their portion of their host OZ census tract remains open to families of all income levels.)

As another example, Minneapolis just took the extraordinary step of doing away with single-family zoning altogether, meaning developers can now build higher-density housing anywhere in the city without needing special approval. This should help housing supply keep pace with demand, mitigating upward pressure on prices and rents.