New Jersey Future Blog

Ten Years After Sandy, a Look at Population and Housing Trends at the Jersey Shore

October 25th, 2022 by Tim Evans

Both before and after Superstorm Sandy, the trend at the Jersey Shore has been toward higher home values, a smaller percentage of housing units being occupied year-round, and an increasing presence of retirees among year-round residents. Is the Shore becoming a playground for the rich? And specifically rich retirees?

On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Superstorm Sandy, we took the initiative to examine a looming question: how have New Jersey shore towns changed, in terms of the year-round vs. seasonal nature of their populations and housing stocks, in the wake of such a major flooding event? We are interested in towns that function as second-home or vacation-rental destinations and are dependent on seasonal visitors1, as opposed to year-round towns like Long Branch, Asbury Park, and Atlantic City, which face a different set of issues.

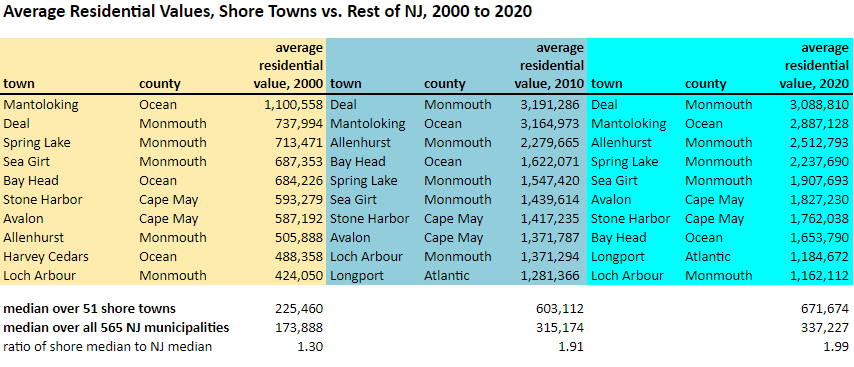

Home values in shore towns are expectedly high, but the differential is getting more conspicuous over time. Among the 51 towns, 38 had an average residential value in 2020 that was higher than the median municipal average of $337,2272 over all 565 NJ municipalities. This is similar to the situation in 2010, when 39 shore towns had average home values that exceeded the municipal median of $315,174. But the number is up from what it was in 2000, when 32 shore towns were above the municipal median. The upward trajectory of home values at the shore relative to the rest of the state was in place well before Sandy made landfall in 2012.

The values in these shore towns are not just high, they are significantly higher than the state median municipality’s average value. Among the 38 shore towns with 2020 average home values that exceeded the median municipal value, a full 25 of them had average values that were more than double the average value in the median municipality. Only 75 municipalities in the entire state exceeded this threshold, meaning that one-third of these high-value places statewide are shore towns, even though the shore towns make up fewer than one in ten municipalities overall. Among the 23 municipalities statewide having an average residential value of more than $1,000,000 in 2020, 13 were Shore towns, including eight of the top 11 (Deal, Mantoloking, Allenhurst, Spring Lake, Sea Girt, Avalon, Stone Harbor, and Bay Head).

Direct access to the ocean appears to be driving housing values. Most of the 13 Shore towns in which the 2020 average residential value is not higher than the median municipality’s tend to be the ones with substantial inland territory (e.g. Stafford, Ocean, and Eagleswood townships in Ocean County and the large mainland townships of Cape May County) and/or which front mainly on a bay rather than directly on the Atlantic (e.g. West Wildwood, Ocean Gate). In other words, most of the lower-value shore towns are places where few if any homes are within walking distance of the Atlantic Ocean itself, and even if you live “down the Shore,” you still drive to the actual beach. The only exceptions are Seaside Heights, Ventnor City, and Wildwood. By and large, if most or all of a town’s territory is on a barrier island, or it fronts on the ocean in the part of Monmouth County where there are no barrier islands, then its home values are going to be higher than average, often significantly higher.

Many of these homes are not lived in year-round. All 51 of these shore towns have vacancy rates that are higher than the statewide rate by virtue of how we are defining “the Shore,” but the trend is toward a greater percentage of housing units being occupied only seasonally, whether as second homes or as summer rentals. (Homes that are not occupied in the off-season are counted as “vacant” by the Census Bureau, even if they are lived in for part of the year.) Among the 51 shore towns, the median housing vacancy percentage has crept steadily upward, from 41.2% in 2000 to 48.6% in 2010 to 54.0% in 2020. So as of 2020, more than half of these shore towns are more than half empty in the off-season, hinting at a decline in the number of year-round residents.

As the percentage of housing units occupied only seasonally has trended upward, year-round populations have in fact trended downward. The 51 shore towns as a group saw their number of year-round households decrease by 2.6% from 2010 to 2020, even as the number of households statewide increased by 3.0%. Among the 51 towns, more than two-thirds (36) experienced absolute decreases in the number of households, and an additional five increased at a slower rate than the state. Most of the 10 towns in which the number of households increased faster than the statewide rate are among those with mostly inland territory, where home values also tended to be lower and where population growth is most likely not taking place in the oceanfront areas.

Year-round Shore residents are increasingly likely to be retirees. In 2000, the median percent of residents age 65 or older among the 51 shore towns was 22.3%, increasing to 25.0% in 2010 and further to 31.8% in 2020. The percentage of people age 65+ statewide increased from 13.2% in 2000 to 13.5% in 2010 to 16.2% in 2020, as the huge Baby Boom demographic cohort has begun aging into retirement, but the increases have been more dramatic at the Shore. In 2020, 14 of the 51 shore towns had a 65+ percentage of 40% or more, up from only eight in 2010 and only one such town (Cape May Point) in 2000.

Rising residential values, an increasing share of housing units being occupied only seasonally, and the increasing presence of people age 65 and older among year-round residents all point to Shore towns becoming increasingly off-limits for year-round occupancy for all but wealthy retirees. This raises fundamental questions about the future of the Jersey Shore. Given the risks from sea-level rise and climate change more generally, who will be able to live at the Shore on a part-time or year-round basis? Should there be a stable or growing population at all? Will only wealthy people be able to afford to move there? And will these wealthy residents be required to rebuild with their own money the next time disaster strikes? These are all questions that state decision-makers should be considering, perhaps as part of a much-needed update to the State Development and Redevelopment Plan.

__________________

1We define the 51 “Jersey Shore towns” as municipalities along the Atlantic coastline (as opposed to the Raritan and Delaware bays) in Monmouth, Ocean, Atlantic, and Cape May counties in which at least 10% of housing units were tabulated as “vacant/seasonal” by the Census Bureau in 2010. (The Census Bureau did not distinguish seasonally vacant units in 2020.) The full list of Shore towns by county:

Monmouth County: Allenhurst, Avon-by-the-Sea, Belmar, Bradley Beach, Deal, Lake Como, Loch Arbour, Manasquan, Monmouth Beach, Sea Bright, Sea Girt, Spring Lake, Spring Lake Heights

Ocean County: Barnegat Light, Bay Head, Beach Haven, Eagleswood Township, Harvey Cedars, Island Heights, Lavallette, Little Egg Harbor Township, Long Beach Township, Mantoloking, Ocean Gate, Ocean Township, Point Pleasant Beach, Seaside Heights, Seaside Park, Ship Bottom, Stafford Township, Surf City, Toms River, Tuckerton

Atlantic County: Brigantine, Longport, Margate City, Ventnor City

Cape May County: Avalon, Cape May, Cape May Point, Lower Township, Middle Township, North Wildwood, Ocean City, Sea Isle City, Stone Harbor, Upper Township, West Cape May, West Wildwood, Wildwood, Wildwood Crest

2 To clarify, each of the 565 municipalities has an average residential value, and the median of those 565 averages is $337,227

New Jersey Future Shapes and Supports New Flood Disclosure Legislation

October 21st, 2022 by Kimberley Irby

New Jersey Future’s Kim Irby and Peter Kasabach testifying at the August 11, 2022 joint Assembly and Senate Environment Committee hearing. Photo Credit: Hannah Reynolds

New Jersey has started down the path to join 29 other states that require home sellers to disclose past flood damages to potential buyers. Senate Bill 3110, which would benefit renters in addition to homeowners, was introduced last week at the Senate Environment and Energy Committee hearing on Thursday, October 6. This bill took shape two months after a joint Assembly and Senate Environment Committee hearing in which New Jersey Future testified on the need for robust flood disclosure legislation. In addition to New Jersey Future, Environment New Jersey and the Coalition for the Delaware River Watershed testified in support of flood disclosure transparency, while the New Jersey Apartment Association testified against the bill, suggesting a few changes to the portion relevant to landlords.

The destruction wrought by the remnants of Hurricane Ida in 2021 is still fresh in the state’s memory, and, even more recently, the remnants of Hurricane Ian caused flooding issues along the Jersey Shore just days before the committee hearing. Mandating flood disclosure is a common sense action for a state with coastal and inland flooding risks that are increasing due to climate change. Improving consumer transparency through this law will not only benefit current renters and homeowners, but also future generations who seek to locate in newly designated flood zones as FEMA and insurance companies update their maps. Ultimately, this legislative action will help save current and future New Jerseyans money and stress in the long term.

New Jersey Future worked through the Rise To Resilience Coalition and with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) to advance specific flood disclosure requirements to both the New Jersey seller’s property disclosure statement and lease agreements. This work, also done in consultation with relevant stakeholders such as New Jersey Realtors, culminated in this bill, which will hopefully undergo a smooth process to reach the finish line.

Earlier this year, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) published a report that estimated far higher damage costs to previously flooded homes in comparison to homes that had not been flooded. In response to that report, Pete Kasabach said: “New Jersey is the most developed state in the nation. This intense development coupled with the experiences of [Hurricanes] Sandy and Ida have demonstrated just how vulnerable our coastal and riverine communities are to flooding… It is well past time that New Jersey residents get the most complete and timely information about flood risks before they rent or purchase a home.”

The Senate bill was unanimously voted out of committee, with amendments, and now makes its way to the Senate floor, with an Assembly version assumed to be forthcoming. If the bill is signed into law at the Governor’s desk, as is widely anticipated before the close of this legislative session, New Jersey Future will work to ensure implementation is swift. It is past due time that all New Jersey homeowners or renters can consider the extent of their flood risk before choosing the place they will make their home.

Clean Water in the Garden State: Reflecting on 50 years of Progress and Challenges

October 18th, 2022 by Lindsey Sigmund

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the monumental piece of legislation known as the Clean Water Act (CWA). The CWA plays an important role in cleaning water pollution and protecting healthy waterways in the State of New Jersey for drinking water supply, healthy habitat for fish and wildlife, and economic and recreational activity. As we look ahead, we also acknowledge the work that still must be done to ensure that the CWA’s legacy is lived out in full.

In response to growing concerns over the quality of our nation’s bodies of water, the federal government passed the CWA in 1972, an amended version of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948. The CWA established the structure for regulating the discharge of pollutants into the waters of the United States and regulated water quality standards of surface waters and wetlands. Prior to the passage of this landmark legislation, there was minimal regulation of what could be dumped into our waterways, which led to polluted rivers and lakes, contaminating many sources of drinking water and causing serious impacts for human health. Thankfully, today, it is unlawful for any pollutant to be discharged from a point source into navigable water without obtaining a permit.

Delaware River, Trenton, NJ, 2022. Photo Credit: Alyssa Zabinski, New Jersey Future

Since the 1970s, a significant volume of pollutants have been better managed, more lakes and rivers are fishable and swimmable, and the overall health of our waterways and wetlands has improved. However, progress has not been linear. Even today as we watch the Sackett v. EPA case unfold in the Supreme Court—where the classification of which bodies of water are considered waters of the United States (WOTUS) and thus can be regulated under the CWA is being determined—it is clear that the specifics of the CWA’s power have been largely contested. Over the past few decades, the Supreme Court and presidential administrations have restricted or reinstated protections for wetlands, streams, and other bodies of water. While battles may ensue on the federal level, New Jersey has been fairly consistent, going beyond minimum federal standards to protect the quality of our water resources.

One of the benefits of the CWA was the establishment of shared responsibility between the federal government and the states for regulation of waterways. For example, the CWA includes the option for states to assume the management of the Section 404 permit program to regulate dredge or fill material for certain waters not preempted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. New Jersey is one of the few states that formally manage the permit program and acts as an example for other states working through clean water regulatory issues. While CWA enforcement is shared by the EPA and states, states have primary responsibility of ensuring compliance is achieved and programs are tailored to the unique needs of their communities.

A prime example of New Jersey’s leadership around clean water is the work of late Governor James Florio. As a congressman in the 1970s, Florio fought for the passage of the CWA. As governor, Florio was responsible for the Clean Water Enforcement Act (CWEA) of 1990, which solidified New Jersey’s commitment to water quality protections. The CWEA requires the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) to inspect permitted facilities and municipal treatment works annually. The CWEA is an excellent example of the reinforcement and reinstatement of the CWA on the state level.

The passage of the CWA has improved the quality of New Jersey’s waterways through regulating point source pollution, but nonpoint source pollution is still a looming concern. Non-point source pollution is caused by rainfall or snowmelt traveling over impervious cover, such as roads or roofs, carrying pollutants into storm inlets or directly into waterways. With a highly developed state such as New Jersey, retrofitting our impervious cover to include best management practices such as green infrastructure to decrease nonpoint source pollution and improve water quality and reduce flooding, is paramount.

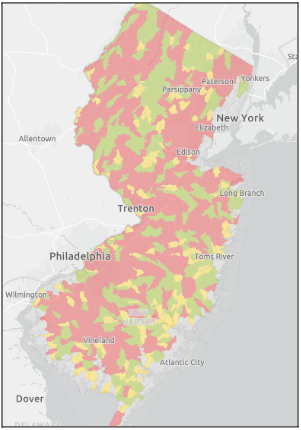

Impared streams in New Jersey shown in red (NJ Water Risk Equity Map, Rutgers University, Jersey Water Works)

In 2020 NJDEP published a new set of stormwater management rules that require the use of green infrastructure for new development. Prior to the rule change going into effect March of 2021, New Jersey Future, along with our partners, advocated for strengthening said rules to capture additional projects that increase impervious cover in order to better manage stormwater runoff across the state. With the reinforcement of sound research and public support, New Jersey improved its stormwater management rules and further increased protections of our water resources.

To improve current conditions, NJDEP anticipates approving a new and improved Tier A Municipal Separate Storm Sewer (MS4) permit early next year. The draft permit sets forth watershed level planning requirements for municipalities to address stormwater runoff. In response to the draft permit issued in July 2022, New Jersey Future issued comments and provided testimony to emphasize the need for faster implementation timelines and additional technical assistance and guidance from NJDEP to ensure permittees can reach compliance.

Sometimes rule updates, permitting updates, and other statewide initiatives are not always voluntary; at times the federal government gets involved. Through the National Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Policy, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued requirements for all states with combined sewer systems to have their municipalities mitigate their combined sewer overflows through projects outlined in a Long Term Control Plan (LTCP). The LTCP outlines the most cost-effective manner to regulate CSOs to meet water quality standards. For the past few years, the Sewage Free Streets and Rivers campaign, staffed by New Jersey Future, has brought together grassroots organizations and residents of environmental justice communities with combined sewer systems to advocate for compliant LTCPs and robust community engagement around the planned water infrastructure projects. The LTCPs have been submitted to NJDEP, however these submittals have not been formally approved. The contents of these plans and their implementation will drive major infrastructure overhauls in 21 municipalities that currently experience overflow events that degrade their waterways. The results should drastically improve water quality, however the issue of funding and who foots the bill is ever-present.

In addition to permitting, NJDEP provides funding for local stormwater management projects through the 319(h) provision of the CWA. Earlier this year, NJDEP awarded $9.4 million in grants to municipalities, nonprofits, universities and others to fund local stormwater management projects. Municipalities including Newark, Trenton, and Jersey City received funding for tree plantings, green infrastructure, and other public improvements to manage stormwater to restore and protect water quality in their watersheds. Despite these funding sources, there is still a significant gap in funding, especially for overburdened communities. With the passage of the American Rescue Plan (ARP) in 2021, New Jersey allocated $300 million of its relief package to fund critical water infrastructure. However, additional outreach and technical assistance is needed to ensure that this infrastructure funding reaches overburdened communities. It is imperative that green infrastructure and other water infrastructure improvements are implemented in New Jersey’s overburdened communities, where improved management of our contaminated water legacy will make for healthier communities.

While great strides have been made in the past half of a century, many of our state’s waterways are still considered impaired, as indicated in the map above. Many of these waterways are contaminated from historic industrial uses, unregulated non-point source pollution, and mismanaged water and sewer infrastructure. All of these contributing factors are further exacerbated by climate change and related increasing temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns. As New Jersey grapples with our industrial past, surface and drinking water impairments, climate change, and environmental injustices, there is still a great need to progress further toward the original intent of the Clean Water Act. Here’s to the next 50 years of working toward fishable and swimmable waters for everyone in the Garden State!

New NJF Report Explores How to Promote Racial Integration in NJ Municipalities

September 22nd, 2022 by Tim Evans

Jersey City, NJ

New Jersey is paradoxically one of the most diverse and most segregated states in the nation. The state has grown more diverse over the last two decades, with its non-Hispanic white percentage shrinking from two-thirds of the state population in 2000 to a little more than half as of the 2020 Census, with notable proportional growth among Hispanic and Asian-American communities. But New Jersey’s macro-level diversity often does not translate into integration at the local level, and places that are integrated at the local level don’t always stay that way. New Jersey Future’s new report, “Promoting and Maintaining Racial Integration: Lessons from Selected New Jersey Towns,” examines what towns can do and have done to foster stable racial integration since 2000.

To explore possible answers, New Jersey Future summer intern Isabel Yip researched examples of New Jersey towns that have achieved and maintained an above-average level of diversity over two decades, to see what state and local leaders and policy makers might be able to learn from them. With advice from some of New Jersey Future’s professional colleagues who have experience in promoting integration and fighting discriminatory land-use practices, Isabel gathered information and insights from local officials, housing advocates, and engaged residents from a set of seven case-study municipalities that have engaged, in one way or another, in efforts to promote racial inclusivity.

These municipalities included:

- Montclair: The legacy of redlining recedes as demand grows for walkable and transit-oriented development–and raises concerns about displacement.

- Asbury Park: A town with a recent history of inclusion now struggles to maintain its diversity in a changing market.

- Cherry Hill: A former destination for “white flight” embraces diversity.

- South Orange and Maplewood: A coalition of residents from two neighboring towns demonstrates the value and importance of active and continuous engagement on integration.

- Jersey City: The state’s most diverse municipality finds that diversity is not a static concept.

- Pennsauken: Community engagement is important – and so is diversity in leadership.

Yip and New Jersey Future found that the concept of “stability” is elusive, and that promoting integration is an ongoing process that requires consistent attention and dedication from civic leaders and community members. Other themes that emerged from her fact-finding effort included policies like inclusionary zoning ordinances to maintain housing affordability, community engagement by public-facing agencies like police departments and school boards, and the creation of spaces in communities that promote casual interactions among people of diverse backgrounds. As the public becomes more aware of the degree to which local decisions about housing and land use affect who your neighbors are, the lessons and methods captured in this report indicate areas of success and improvement for municipalities and communities to adopt or avoid.

Read the full report here.

Next Steps for Warehouse Planning – and Regional Planning More Broadly

September 21st, 2022 by Tim Evans

The State Planning Commission has adopted new warehouse siting guidance. The next step should be to translate the principles articulated in the guidance into a map indicating the best places for future warehouse growth to take place.

The State Planning Commission has adopted new warehouse siting guidance. The next step should be to translate the principles articulated in the guidance into a map indicating the best places for future warehouse growth to take place.- In preparing the map, the Office of Planning Advocacy should coordinate with the New Jersey Department of Transportation, which is preparing a Freight Plan that will address freight as it moves over the transportation network.

- State efforts to address warehouse growth are serving to highlight the importance of statewide planning—and the long-dormant State Development and Redevelopment Plan—in channeling future growth in a way that makes efficient use of infrastructure and resources while also preserving the state’s quality of life.

The State Planning Commission at its Sept. 7 meeting officially adopted the Warehouse Siting Guidance drafted by the Office of Planning Advocacy (OPA) earlier this summer, intended for use by municipalities in deciding how best to plan for warehouse developments. With the rapid growth of the goods-movement industry in New Jersey in recent years, more municipalities will need help sorting through the issues involved, which the officially adopted Warehouse Siting Guidance is intended to provide.

While the guidance document offers much-needed assistance to local officials who are struggling to anticipate the likely effects of warehouse development, none of its recommendations are mandatory—New Jersey remains a “home rule” state where local governments have authority over land-use decisions. For municipalities that may be interested in operationalizing some of the concepts laid out in the guidance, OPA staff are working on a model ordinance and will be seeking feedback on it in the coming months.

Goods movement is a key pillar of New Jersey’s economy. The wholesale trade (NAICS code 42) and transportation and warehousing (NAICS codes 48 and 49) sectors of the economy account for one out of every eight jobs in the state, the highest percentage among the 50 states. By addressing the land-use needs and impacts of a major statewide industry, the warehouse guidance document serves to bring back into the spotlight the importance of regional planning and OPA’s role in promulgating the New Jersey State Development and Redevelopment Plan (“State Plan”), the policies of which are referenced throughout the warehouse guidance.

A logical next step for OPA would be to translate their guidance into a map indicating the locations of potential development and redevelopment sites that best meet the warehouse-siting criteria articulated in the guidance, similar to how the State Plan map illustrates the principles that animate the Plan playing out on the ground. OPA should coordinate with the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT), which is currently working on an update of its Statewide Freight Plan (the most recent edition of which dates to 2017), to identify sites that are optimally situated near the regional transportation network and best able to accommodate the truck traffic that large warehouse buildings attract. If the Freight Plan is concerned with moving freight from one place to another, while a state warehouse plan would be focused on the spaces occupied by freight while it is standing still, each process should be able to inform, and be informed by, the other. Sites that appear well-suited to warehouse development from a transportation standpoint could then be compared to map layers illustrating other relevant constraints, like the locations of prime farmland or of lower-income communities already suffering from poor air quality.

A statewide warehouse map and its accompanying analysis could serve as a stand-alone product or could be incorporated into a broader (and overdue) revision of the whole State Plan, which has not been updated since 2001. The point of the State Plan has always been to anticipate future growth and determine how and where to accommodate it in a way that makes the most efficient use of state resources while also preserving the state’s quality of life. These are the questions that shippers and industrial real estate developers are presently confronting with respect to warehouses, but the questions are not unique to the goods-movement industry.

Much has changed about New Jersey’s development landscape in the last 20 years. Targeted growth areas, transportation corridors, land preservation priorities, and redevelopment opportunities all need to be updated to reflect current conditions. Future growth strategies also need to reflect threats from climate change, which Superstorm Sandy, Hurricane Ida, and other major weather events have brought to the fore in the two decades since the State Plan was last updated. If state agencies are to target infrastructure investments and development incentives—whether for warehouses, residential growth, or any other type of development—to places where they best advance the state’s vision of its own future, a new edition of the State Plan would give them an up-to-date baseline from which to work. For these reasons, and more, New Jersey Future supports a robust and inclusive update of the outdated State Plan.

New Jersey Future Provides Direction at Joint State Senate and State Assembly Climate Hearing

August 16th, 2022 by Hannah Reynolds

“As New Jersey works to advance decarbonization and resilience efforts, we must ensure that residents are able to make informed decisions for themselves, and their families, in the wake of growing climate risks,” said New Jersey Future (NJF) Policy Manager Kim Irby, at the August 11th joint legislative committee hearing hosted by State Senator Bob Smith (D-17) and State Assemblyman James Kennedy (D-22) last Thursday. She continued, “New legislation with long overdue reforms would ensure that New Jersey homebuyers, renters, and business owners are fully informed about the ever-increasing risks of flooding so that they can protect their belongings and families.”

Kim Irby and Pete Kasabach (NJF) providing testimony to the joint committee on environment last Thursday. Photo Credit: Hannah Reynolds

Irby’s remarks, accompanied by an introduction and conclusion from NJF Executive Director Pete Kasabach, were part of a joint hearing on the environment and climate change, with representatives from the New Jersey State Senate and State Assembly present. The testimony outlined added costs of the growing threat of flooding for New Jersey homes and communities, before introducing the potential for flood disclosure laws to help inform buyers of risks of flooding associated with the properties they purchase. Presently, Irby informed the committee, flood disclosure laws in New Jersey fall significantly below the nationwide standard. Irby and Kasabach suggested that the legislature take steps to build transparency around flood disclosure, including requiring data to be available surrounding historical flood data, flood projections, and flood insurance status, to name a few. All six official recommendations are listed in NJF’s testimonial, available online.

As NJ grapples with drought and braces for an impending storm season, the joint Senate Environment and Energy Committee and the Assembly Environment and Solid Waste Committee hearing examined an array of legislative approaches to addressing climate change. The testimony on flood disclosure proved to be very timely and important within the broader context of the hearing. Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Shawn LaTourette opened the meeting with remarks on the growing impacts of climate change and the need for urgent political support to mitigate growing climate risk, including flooding, stormwater management, and rising sea levels. Other environmental advocates presented concerns around coastal resilience and sustainable development in coastal NJ communities. Finally, the legislature heard public testimony on two proposed bills related to renewable energy portfolios and fossil fuel divestment.

The hearing offered an opportunity to address the widespread risks of climate change experienced in New Jersey, and the flood disclosure testimony from NJF staff contributed meaningfully to the diverse dialogue on climate and environmental issues across the state. In all, as Commissioner LaTourette explained, “There is no one silver bullet that will protect every community… There is, however, a network of solutions that will ensure the resilience of our communities and economies in the face of a changing climate.” Improved flood disclosure laws offer one such solution.

Meet New Jersey Future’s 2022 Summer Interns!

August 9th, 2022 by New Jersey Future staff

New Jersey Future’s internship program is developing the next generation of thinkers in smart growth. We offer graduate and undergraduate students the opportunity to assist us with various projects, including research, writing, communications, and administration. We appreciate their wide-ranging contributions! See a list of our previous interns and learn how to apply.

Here is what this summer’s interns worked on, in their own words.

Claire Brennan

Temple University

Field of Study: Journalism

I had the pleasure of working alongside Mo Kinberg and Chris Sturm on the Clean Water, Healthy Families, Good Jobs campaign, working alongside a coalition of environmental, business, and labor groups lobbying for Governor Murphy and the legislature to designate American Rescue Plan (ARP) funds to rehabilitate New Jersey’s outdated water infrastructure.

The beginning of my internship focused on gathering information on municipalities that suffered from combined sewer overflows (CSOs), lead-lined pipes, and drinking water utilities contaminated by forever chemicals called PFAS. This research was used to gauge which legislative districts had the widest array of infrastructure issues, and ultimately, as prep for meetings with the legislators of these districts.

Once much of the groundwork of the campaign was laid, I focused on communicating with endorsing members and alerting them of upcoming events and ways to help advance the campaign. I also reached out to legislators to inform them of issues surrounding New Jersey’s failing utilities, and the opportunity that ARP funds provided to begin fixing them.

While working on the campaign, I’ve garnered research skills, a wealth of knowledge on water infrastructure, and the confidence to communicate the importance of its vitality. I feel privileged to be a part of a campaign to keep people healthy, and to see our coalition’s values reflected in the legislature’s budget.

Aishwarya Devarajan

College of the Atlantic

Field of Study: Human Ecology, Policy

My name is Aishwarya Devarajan, a sophomore at the College of the Atlantic, and an intern with New Jersey Future (NJF). Through my time with NJF I have had the opportunity to interact with many local experts in multiple states to learn about the implementation of green and complete streets. Throughout these meetings, I have witnessed the relentless passion of advocates for complete and green streets, who care about people and the planet. As our streets get more crowded and more polluted, disparities within populations grow, decreasing accessibility within our communities. Complete and green streets are community hubs that bring accessibility, safety, sustainability, stormwater management, and economic benefits. The New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) has the ability to help these advocates create safe streets for communities to enjoy. NJDOT should incorporate green infrastructure and pedestrian safety measures into state-owned streets, encourage municipalities to implement best practices, and develop new set-aside grants for complete and green streets. New Jerseyans deserve clean air to breathe, safe and accessible streets to get around, and support for local businesses.

Margaux Petruska

Lehigh University

Field of Study: Environmental Policy

This spring, I have been grateful to work as a research intern on the Clean Water, Healthy Families, Good Jobs Campaign for New Jersey Future, under the supervision of Mo Kinberg. Through these few months, I have focused primarily on legislative district profiles and conducting research that was utilized as background knowledge for meetings about the campaign with legislators. I researched information about various NJ districts and learned about their drinking and wastewater infrastructure. I compiled summaries with highlights on problems within districts such as lead service lines, forever chemicals like PFAS, combined sewer overflows (CSOs), and contaminants. Additionally, I delved into data with Jyoti Venketraman separating updated LSLI data into their subsequent utilities. Having just begun my Master’s program, it was incredibly enriching to learn more about environmental and water policies through New Jersey Future while learning about it in my classes. I learned how to work outside of my comfort zone toward a specific goal, such as the campaign.

I am grateful for this opportunity to help me delve deeper into the field of advocacy and the progress it can make, and I hope to continue work as important as this organization does in the future.

Sasha Weber

Barnard College

Field of Study: Urban Studies

My name is Sasha Weber and I’m a senior at Barnard College, where I’m an Urban Studies major with a concentration in Environment and Sustainability. This semester I have been working on the Mainstreaming Green Infrastructure team. Since March 2, 2021, NJ municipalities have been required to utilize green infrastructure as a stormwater management technique on all new public and private developments. My role has been to research municipalities’ updated stormwater ordinances and determine which ones have gone above and beyond New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s requirements to protect communities from flooding and pollution. In my research, I have interviewed representatives from several municipalities to learn more about how they developed their stormwater ordinances. I have also explored case studies highlighting these new requirements in action. I have enjoyed learning about how diverse municipalities have used their resources and considerations of ecological conditions to create these new ordinances and I am excited for the future of green infrastructure as a tool for flood and pollution prevention, urban heat reduction, and ecological resilience.

Isabel Yip

Princeton University

Field of Study: English

Through the Princeton Recognizing Inequities and Standing for Equality (RISE) program, I worked with New Jersey Future on the Geography of Inequality project, conducting qualitative analysis by interviewing key figures in New Jersey towns about economic and racial integration. My research focused on affordable housing, zoning, the use of space to bring people together, and the importance of community relationships in places throughout New Jersey. I spoke with mayors, the leaders of community groups, council members, and city planning officials about how New Jersey towns work towards integration and maintain their diverse identities. With New Jersey Future’s director of research, Tim Evans, I created a report compiling my interviews with New Jersey leaders and research into the town’s history, which documented former hindrances to integration like formerly redlined districts, as well as developments like inclusionary housing ordinances. The interviews and research I conducted resulted in a series of recommendations for other places in New Jersey in order for them to become more stably diverse and integrated. I am thankful to New Jersey Future, the Princeton RISE program, the community leaders throughout New Jersey who gave me their insight into integration, and to my supervisor Tim Evans, who heightened my understanding of housing in New Jersey and of how the use of space can contribute to socioeconomic inequality.

Amidst rising pedestrian and traffic fatalities, New Jersey seeks to advance safe street design

July 19th, 2022 by Michael Atkins

Photo Credit: City of Hoboken

Street fatalities are on the rise nationally, and right here in New Jersey. The National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reports that 2021 marked a 16 year high in roadway fatalities. In New Jersey, our streets and roads claimed 699 lives in 2021, with 220 pedestrian fatalities accounting for approximately 30% of those fatalities. This pace shows no signs of slowing this year: “318 people have been killed on New Jersey’s roadways [as of July 2022], already an 18% increase from last year’s historically high rates.” This deadly trend has arisen even as commutes remain disrupted from the coronavirus pandemic, with more people opting out of the daily commute to work from home or remotely. In short, while less driving should be associated with fewer fatalities, we have observed the opposite effect, both locally and nationwide. Even with less car travel overall, the increase in fatalities reveals the need to focus on the development of safe streets in our broader efforts to help people drive less.

This month, Smart Growth America released its Dangerous By Design Report for 2022, which paints a stark picture of our lack of progress on street safety nationally and in New Jersey by delving deep into the 2021 statistics on crashes throughout our roadway systems. The results depict New Jersey as the nineteenth most dangerous state in the United States when it comes to street safety.

Pedestrian fatalities directly relate to street design that prioritizes automobile speeds and places pedestrians and cyclists in conflict with larger, faster, deadly vehicles. Conditions that pose the greatest risks to pedestrian safety include places without sidewalks, crosswalks, street lighting (as is common in areas of South Jersey), or urban areas where pedestrians and cyclists must compete with an array of motorized vehicles along busy city arterials(common in North Jersey). As the report states, “Lower-income neighborhoods are much more likely to contain major arterial roads built for high speeds and higher traffic volumes at intersections, exacerbating dangerous conditions for people walking.” In New Jersey, as throughout the United States, these lower-income neighborhoods are predominantly communities of color facing economic hardship and historic disinvestment.

One commonly dangerous type of roadway found throughout New Jersey is what is known as the “stroad”. The term “stroad” was coined to express the conflict within modern traffic engineering to balance “street” uses, like commerce, temporary parking, and property entrances, with “road” usage, where high speeds are prioritized to connect vehicles between longer distance destinations. Stroads often lack sidewalks and crosswalks, and are particularly dangerous for pedestrians and multi-modal transit users. New Jersey has developed dozens of stroads throughout the state—in part, our famous jughandles are aimed at reducing conflicts on stroads between drivers making turns across oncoming traffic.

Despite the predominance of stroads, not every corner of the state is facing a pedestrian fatality crisis. We need look no further than Hoboken to find a city that has managed four years without a pedestrian fatality. The City of Hoboken has made a concerted effort to transform its streets during standard repaving efforts into complete streets, facilitating safe crossings for pedestrians, bicyclists, and importantly, people with disabilities who use a walker or a wheelchair when traversing urban streets.

The attention to street safety and fatality rates is increasing in tandem with a greater focus on “Vehicle Miles Traveled” (VMT), a measurement that advocates assert provides more information than measurements of congestion, speeds, or greenhouse gas emissions alone. Looking closely at VMT in tandem with land use patterns can assist planners and transportation agencies in reducing car trips overall (along with congestion and fatalities), by informing decision-makers about where to build denser housing and mixed-use developments, reduce speeds, add bus-only lanes, or expand public transit options.

“New Jersey Future believes that safe street redesign and embracing vision zero principles will facilitate lower fatalities, vehicle miles traveled, and greenhouse gas emissions,” said Tim Evans, research director with New Jersey Future in a statement released in response to Smart Growth America’s Dangerous By Design report.

State Senator Diegnan and Assemblyman Karabinchak introduced a bill in June 2022, S2885/A4296, which would establish a Vision Zero Task Force to address traffic safety for all road users by prioritizing “access, equity, and mobility” and to advise state leaders and agencies on policies and programs to “help achieve the goal of zero traffic fatalities and serious injuries” on New Jersey’s streets and roadways.

“At the end of the day, this all boils down to lives on the line. We have an imperative to reduce fatalities on our streets with safe design, just as we have a duty to cut our greenhouse gas emissions by reducing car trips and vehicle miles traveled. If we want people to drive less, we need to make safe places for people to travel without a car. Fostering safer street design will encourage people to consider multi-modal and low-emission transportation options by making walking, biking, and scooter trips more inviting to New Jerseyans,” stated New Jersey Future’s executive director, Peter Kasabach.

Opportunity to Participate in a Pilot Program to Track Vehicle Miles Traveled in New Jersey

July 19th, 2022 by Kimberley Irby

Image Credit: The Eastern Transportation Coalition

Did you know that a fuel tax you pay at the pump is largely responsible for funding a well-functioning transportation system that gets you to where you need to go, delivers packages to your door, and keeps groceries on the shelves? But as vehicles go farther on less fuel and some stop using any fuel at all, it becomes harder to maintain our aging transportation system.

The Eastern Transportation Coalition, a partnership of 17 states and Washington D.C., needs your help to explore an alternative approach, called a Mileage-Based User Fee (MBUF), which means each driver pays for the miles they drive instead of the fuel they buy.

In addition to being a viable alternative to fuel tax funding, it could also help New Jersey track where and how much driving is happening. This, in turn, could be incredibly helpful as the state promotes less car dependency in the pursuit of co-benefits such as reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and greater access and affordability.

To better understand how a Mileage-Based User Fee program could work, the Coalition is conducting a Pilot Program in New Jersey and they want you to join and tell them what you think! It is free to participate, and there are strict privacy protection measures to safeguard your data.

Here’s how to join the Pilot in four easy steps:

- Enroll – Fill out the enrollment form by clicking the link on the website.

- Insert – Plug a small device into your vehicle to record mileage.

- Drive – Then drive as you normally do.

- Return – After a few months, mail back the device.

Image Credit: The Eastern Transportation Coalition

*These steps may vary depending on the mileage-reporting option selected.

Your voice is important, so visit NewJerseyMBUFpilot.com to learn more and enroll. Participants who qualify can receive up to $100. Have questions? Contact a Pilot team member at 609-293-7800 or by email (NewJersey MBUFpilot

MBUFpilot org) .

org) .

The Risk to Our Roofs: Considering and Harnessing the Climate-Housing Nexus

July 11th, 2022 by Michael Atkins

Plenary session “The Risk to Our Roofs: Considering and Harnessing the Climate-Housing Nexus” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

New Jersey faces major challenges with the dual threat of climate change and housing unaffordability. While at face value, these two issues seem to pertain to natural or built environments, respectively, the two are inseparably linked and must be addressed in tandem.

At the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, co-hosted by New Jersey Future and the American Planning Association New Jersey Chapter (APA-NJ), the intersection of housing and the environment was given center stage during the lunch plenary session. This session featured a row of experts in this field, moderated by Thomas Dallessio, Vice President of Policy, APA-NJ.

As the experts enumerated, the idea of forming “resilient cities” is aimed at providing protections for residents and erecting environmental buffers to protect the people housed in climate vulnerable communities. As opening panelist Dana Bourland, senior vice president at the JPB Foundation, outlined, “gray” communities—or the existing impermeable hardscape and car-centric design of many buildings, commercial corridors, and communities—exacerbate inequalities that overburden people of low-income and Black and Brown communities.

Dana Bourland speaking at New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

“Green” developments seek to capitalize upon climate resiliency and carbon sequestration by utilizing recycled materials, alternative energy sources (i.e. solar roofing), and integrative design into the fabric of the community. Through integrative design, low-income and eldery residents can more easily live car-free or conveniently utilize multimodal transportation options that encourage public health and reduce carbon transportation emissions. Bourland is the author of “From Gray to Green: A Call to Action on the Housing and Climate Crises”, a book on this subject recommended to all audience members and readers, and has also developed a publicly available toolkit, “The Green Communities Criteria,” which is available online at greencommunitiesonline.org.

Georgeen Theodore—professor at Hillier College of Architecture and Design of the New Jersey Institute of Technology—shared a rich presentation that explored best practices in design and redevelopment to foster physical resilience from storms and flooding, focusing on housing development and environmental landscaping in coastal communities. Theodore sought to illustrate techniques to move residents from low-lying flood prone areas to higher ground, by both constructing new resilient housing and providing floodplain buy back funding for existing residents to assist their move. She also highlighted that floodplain reclamation presents an occasion to develop grassy wetland areas that can serve not only as a buffer between the bay and housing in a storm, but provide access to open space and recreational opportunities for residents through all seasons.

Georgeen Theodore speaking at New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

Kelvin Broddy grounded the entire conversation with real-life, firsthand experiences by sharing his perspective of flooding and housing in Newark. Boddy is director of Healthy Homes and Communities, Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey (HCDNNJ), a statewide membership-based organization with over 270 members including foundations, businesses, community development corporations,and private developers. Together, members work to construct affordable housing that is “healthy in both construction and location.” Affordable housing is too often constructed in undesirable and precarious land, or cordoned off into one section of a city or town. These development patterns leave residents of affordable housing–-who are low-income and/or of Black and Brown communities—vulnerable to not only floods, but extreme heat and poor air quality.

Kelvin Broddy speaking at New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

In the past decade, Superstorm Sandy (2012) and Hurricane Ida (2021) expose the vulnerability of affordable housing units in Northern New Jersey, and the rate we can expect extreme weather events to continue to occur. Boddy pointed to examples in Newark, Elizabeth, and Penns Grove to illustrate the placement of affordable housing in flood-prone areas, or along tributaries that stand to flood regularly in the century ahead.

Not all hope is lost, as Boddy issued a series of solutions proven to address the issue of affordable housing vulnerability to flooding associated with climate change. Primarily, new public and affordable housing should be developed without residences on the ground floor. Existing affordable housing must be preserved, and in some cases restorated, so that cities and towns do not lose their affordable housing stock in the wake of an extreme weather event. Finally, tree plantings and green space improvements in existing and future affordable housing complexes can cool temperatures and improve air quality. Boddy concluded, “With an influx of money from both state and federal governments for the development of affordable housing, it is more important than ever that we ensure both new and old development can meet any challenges the state’s climate presents.”