New Jersey Future Blog

The State of New Jersey’s Housing Market: We Need More

July 11th, 2022 by Tim Evans

Breakout session “The State of Housing in New Jersey” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

New Jersey is facing an acute housing shortage. Nationally, we are millions of housing units short of meeting demand, and the situation is proportionally worse in New Jersey. That was the big-picture message delivered by Debra Tantleff, founding principal of Tantum Real Estate, to kick off the session on The State of Housing in New Jersey at the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, hosted jointly by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association. Demand for housing in New Jersey is far exceeding supply, especially middle-income housing. Failure to produce enough housing, both in terms of the types of housing that potential residents are looking for, and in the kinds of places where today’s homebuyers and renters want to live, puts upward pressure on prices and incentivizes people to look elsewhere.

Adam Gordon, executive director of the Fair Share Housing Center, said that housing unit growth did not keep pace with population growth in the 2010s, particularly because of low production of multi-family housing in the first half of the decade. The slowdown happened in the wake of the 2011 dissolution of the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH), the state agency that had been in charge of overseeing municipal compliance with the Mount Laurel Supreme Court decisions, which require municipalities to allow the creation of housing for low- and moderate-income households. Many towns have chosen to satisfy their Mount Laurel obligations via mixed-income, multi-family projects that include a lower-income component along with market-rate units. The interim between the demise of COAH and the subsequently instituted system of enforcement by lower courts created temporary uncertainty about the determination of municipalities’ obligations, leading to a temporary dropoff in multi-family construction in general.

The lull in multi-family housing production illustrates the extent to which the state implicitly relies on Mount Laurel requirements to provide not just housing for low- and moderate-income households but much of the state’s new middle-income housing as well. Without Mount Laurel, it is not clear how much multi-family housing the state would be producing at all—and it might not be very much, if the rest of the New York metropolitan area is any indication. In the 2010s, the counties of northern New Jersey produced vastly more new housing units per capita than did Long Island, the Hudson Valley, or southwestern Connecticut. This raises questions as to whether relying on the Mount Laurel mechanism is really a sustainable long-term solution for ensuring that the middle class can continue to afford to live in New Jersey.

Fortunately, not all towns take a reactive approach to producing middle-class housing. Scotch Plains is an example of a suburban municipality proactively trying to adapt to evolving market demand for compact, walkable neighborhoods. Thomas Strowe, director of Redevelopment for the Township, spoke about the Township’s recent redevelopment efforts, which are focused on invigorating its small downtown and turning it into more of a mixed-use destination. The Township seeks to make downtown living available to a wider range of households via mixed-income projects that will be enabled by downtown overlay zones and density bonuses. The bonus requires a 20% inclusionary component (that is, 20% of the units must be affordable to low- and moderate-income households), along with public open space and other amenities, thus allowing the Township to address its Mount Laurel obligations while pursuing a broader redevelopment goal. Multiple developers are seeking to take advantage of the bonuses, another sign of the pent-up demand for in-town living.

Breakout session “The State of Housing in New Jersey” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

Meanwhile, on the other end of the spectrum are older, more urbanized municipalities where, until recently, the main problem was not lack of supply but lack of demand for market-rate housing. Tiffany Harris-Delaney, the Director of Policy, Planning, and Development for the City of East Orange, talked about the flurry of recent development projects happening in her city, particularly near its two NJ Transit commuter rail stations. Harris-Delaney pointed to East Orange’s diverse housing stock (84% of its housing units are something other than single-family detached) as a reason the city has long been affordable to a wide range of household incomes, and city leaders would like to keep it that way.

In the face of surging demand for walkable and transit-accessible neighborhoods, East Orange is more vulnerable to the displacement of existing residents than most places, with renters comprising 76% of its households, so together, the City and developers have worked to ensure that new projects incorporate both market-rate and lower-income units, in order to mitigate upward pressure on prices. Gordon said the Fair Share Housing Center has been working with many older urban centers facing similar pressures, encouraging them to adopt inclusionary zoning ordinances–that is, requirements that new residential developments designate a certain percentage of their units for occupancy by low- and moderate-income households–as a way of getting ahead of the displacement issue as market demand returns to cities after decades of absence.

Panelists agreed that cooperation between the public and private sectors makes housing production easier, especially for inclusionary projects. Debra Urban, chief of Multifamily Programs at the New Jersey Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency and the session’s moderator, said that her agency has multiple programs that are designed to help close financing gaps for inclusionary projects, as well as the well-known Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, which has been responsible for facilitating affordable housing projects in a wide variety of places in New Jersey. Tantleff mentioned the importance of payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) and redevelopment area bonds (RABs)—both of which require municipal participation—for making projects cheaper and simpler to finance. She also advised towns to talk to developers in advance about the feasibility of different kinds of housing in redevelopment plans. Strowe pointed out that Scotch Plains has adopted a redevelopment plan for its publicly-owned properties and is soliciting proposals. Tantleff and Gordon each praised both Scotch Plains and East Orange for thinking ahead about the kinds of development they want to see and working with developers to make it happen.

When asked whether the goals of affordable housing advocates and the goals of private developers will continue to coincide over the next 20 years, Tantleff said essentially yes. As Gordon explained, there is so much pent-up demand for housing that it will take a long time for supply to catch up, part of the reason that developers are still able to build for the top of the market in most places. If New Jersey wants to be able to continue to welcome or retain people of all income levels, it needs to both produce more multi-family housing at scale, and preserve existing affordable housing supply. This may involve considering statewide zoning reform, in addition to relying on the Mount Laurel system to incentivize the production of middle-income housing options, and it may mean that inclusionary zoning ordinances should become the rule rather than the exception, in order to avoid displacing existing residents. One way or another, New Jersey needs to find a way to break its housing supply logjam. As Gordon put it, “We shouldn’t need subsidies to produce a $500,000 house.”

State Agencies Shape Infrastructure Programs to Address 21st Century Challenges

July 11th, 2022 by Chris Sturm

Plenary session, “Addressing Key Redevelopment Challenges and How New Federal Funding Will Help Us Get There” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

Communities Advised to Prepare Now to Access Funds

With a record state surplus and billions of dollars of federal funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), New Jersey communities enjoy a rare opportunity to address redevelopment challenges, explained Peter Kasabach, New Jersey Future’s executive director. But a “lack of readiness” will be their biggest obstacle to accessing those funds, asserted New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) Commissioner Shawn LaTourette. He and co-panelists Preethy Thangaraj, policy advisor to Governor Murphy, and Tim Sullivan, CEO of the state’s Economic Development Authority, each described their various approaches to harnessing the new federal funds at the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference plenary session, Addressing Key Redevelopment Challenges and How New Federal Funding Will Help Us Get There.

Local officials can look to the Governor’s Office for information and guidance on new federally-funded programs, according to Preethy Thangaraj. A soon-to-be-launched website will act as a central source for IIJA opportunities, including $2.5 billion in discretionary grant opportunities for transportation, water, broadband and green and complete street projects. Newly appointed Infrastructure Coordinator Richard Sun is connecting locals with state agency staff who can help them apply for funds.

Tim Sullivan noted that the bulk of IIJA funding for New Jersey will come to the state through the federal Surface Transportation Reauthorization Act. The remainder is dedicated to water, energy, and broadband infrastructure, with some monies for workforce development. Together with the state’s share of funding from the federal American Rescue Plan, Sullivan argued that these monies could enable the state to completely finish work on certain issues such as lead in drinking water, so “kids don’t need to drink that water ever again.”

Plenary session, “Addressing Key Redevelopment Challenges and How New Federal Funding Will Help Us Get There” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

Can IIJA funds help the government focus on the future and prepare for rising sea levels and more extreme precipitation? Commissioner LaTourette explained that the NJDEP will use the new funding to change the “mechanics” of modernizing infrastructure by coordinating it with forthcoming interagency climate action plans, updated flood rules, and new spending programs. NJDEP’s share of IIJA funds will go to two areas: long-term flood protection projects for “worst-case scenarios” and local water infrastructure projects that address day-to-day concerns. The agency will funnel $1 billion for water infrastructure projects through the state’s Water Bank as it simultaneously pushes to right-size the state’s share of national water infrastructure funding.

Latourette acknowledged that the Water Bank program “shuts out” some of the communities that are the most in need, so his agency plans to engage engineers and grassroots leaders to help them successfully apply for funding. The department has also formed a Community Investment and Economic Revitalization Program to make opportunities for state-local partnership opportunities clear and available, which includes the agency’s Community Collaborative Initiative program. He added that in the next few weeks the NJDEP would announce grant programs for towns to pursue the creation of stormwater utilities.

Tim Sullivan highlighted three new EDA funding programs that seek to encourage resilient, compact growth and redevelopment:

- Aspire, a gap financing tool for real estate development projects.

- The Historic Property Reinvestment Program, a $50 million competitive tax credit program

- The Brownfields Impact Fund

EDA will receive some IIJA funding for brownfields grants and port infrastructure for off-shore wind in South Jersey. In addition, the governor’s proposed budget provides $25 million for transit-oriented development, $300 million for affordable housing, and funding to integrate climate resilience into the State Development and Redevelopment Plan.

When asked how the state will employ IIJA funds to support historically overburdened communities, Preethy Thangaraj explained that investments will center on policy imperatives in the state’s Environmental Justice Law. For example, the NJDEP map of overburdened communities will be used as a tool to prioritize investments, and the Governor’s Office will rate projects using an equity and sustainability index.

Deploying federal infrastructure dollars in New Jersey will be a team effort between proactive local governments and well-organized state agencies. Communities should prepare now by hiring grant writers to apply for funding and then planners, engineers and architects to design projects and manage construction. The benefit: infrastructure and redevelopment that is ready for growing challenges like climate change.

Social Determinants of Health: National and Local Perspectives

July 11th, 2022 by Jyoti Venketraman

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age that shape their health and well-being. In other words, these are the non-medical factors that impact health outcomes. Social determinants of health include traditional planning domains such as transportation, housing, green spaces, and social domains like good schools and access to good jobs.

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age that shape their health and well-being. In other words, these are the non-medical factors that impact health outcomes. Social determinants of health include traditional planning domains such as transportation, housing, green spaces, and social domains like good schools and access to good jobs.

At the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, co-hosted by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey Chapter of the American Planning Association, a session titled “Social Determinants of Health: National and Local Perspectives” examined and addressed racial and health inequities through planning, policy, community organizing, and culture change by showcasing national and local perspectives. Speakers included Vanessa Barrios, the manager of Advocacy Programs at Regional Plan Association; Michael Kolber, senior planner for the City of Trenton; and Melanie Hughes McDermott, senior researcher with Sustainable Jersey at the Sustainability Institute at The College of New Jersey. The session was moderated by Pamela Russo, senior program officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“Social determinants of health provide an opportunity for planners to have an expanded scope when it comes to redevelopment. In order to achieve sustainability one must incorporate equity.” said Pamela Russo, setting the stage for the session, and inviting viewers into this vital conversation.

Panelist Vanessa Barrios showcased the national perspective on how the Regional Plan Association (RPA) has integrated this lens of social determinants of health. In her presentation and comments, Barrios explained, “Health is integral to well-being. Racial justice, health equity are very vital to regional planning.” Barrios went on to stress how planners make vital decisions that shape the built environment, which in turn impacts the health and wellbeing of all communities. Using the example of RPA’s Healthy Regions Planning Association, Barrios showcased work happening nationally in 10 regions. The regions are exploring how race and racism impacts the built environment through planning, and seek to center community voices in their design process of planning. One takeaway Barrios shared was how by intentionally centering the voices of impacted communities, health equity can be integrated into regional planning to improve health outcomes.

Panelist Melanie Hughes shared a state-level perspective, highlighting Sustainable Jersey’s Gold Star in Health standard, a voluntary program for NJ municipalities. To obtain a Gold Star in Health certification, towns must use existing data, engage multi-sector stakeholders, and connect the dots between social determinants of health and potential action solutions, like access to green spaces and safe streets. Hughes shared that through their work with the Gold Star program, intersection of health and housing, Sustainable Jersey includes housing as an action area, developing a suite of actions that promote healthy housing, with a particular focus on lead poisoning.

Panelist Michael Kolber highlighted the local perspective of the City of Trenton, which was the first city in 2021 to have a Community Health and Wellness plan as part of its master plan. Kolber explained, “Everything in Trenton revolves around our master plan—housing and land use, public safety, arts and culture, [and] health.” Trenton’s Community Health Plan includes many goals, such as increasing access to food, increasing physical activity, improving access to health care, and focusing on seniors, to name a few. Trenton’s planning and zoning meetings use this health plan as part of land use applications review to determine whether the plan relates or justifies development. Decisions like removing grocery store barriers, permitting primary care facilities in all land zones, exploring equitable distribution of parks, and addressing barriers to parks that some face were shared as examples of how community health plans enable integration of health equity in planning decisions at the local level.

The panel and the discussion brought up common themes that were shared across the examples highlighted, including the vital role of cross-sector partnerships, building cross-sector consultative grassroots work, intentionally centering the voices of impacted communities in planning, and learning from past mistakes to rebuild trust. As billions of dollars for infrastructure investment begin flowing into communities across the nation, healthier and more equitable communities can be achieved when racial and health inequities are addressed through planning, policy, community organizing, and cultural change.

Warehouse Development: Regional Significance Calls for Regional Perspective

July 11th, 2022 by Tim Evans

Industries devoted to the movement and storage of goods are a pillar of New Jersey’s economy, providing jobs to nearly one out of every eight employed New Jersey residents. Growth in e-commerce and in the volume of international trade arriving at the country’s second-busiest port, the major facilities of which are located in North Jersey, are creating unprecedented demand for warehouse space. At the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference—hosted jointly by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association—a session titled Warehouse Development: Regional Significance Calls for Regional Perspective drew attention to the importance of the industry, and offered advice to towns scrambling to figure out how to deal with warehouse development proposals.

Industries devoted to the movement and storage of goods are a pillar of New Jersey’s economy, providing jobs to nearly one out of every eight employed New Jersey residents. Growth in e-commerce and in the volume of international trade arriving at the country’s second-busiest port, the major facilities of which are located in North Jersey, are creating unprecedented demand for warehouse space. At the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference—hosted jointly by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association—a session titled Warehouse Development: Regional Significance Calls for Regional Perspective drew attention to the importance of the industry, and offered advice to towns scrambling to figure out how to deal with warehouse development proposals.

Jim Gilbert, a member of New Jersey Future’s Board of Trustees and a former chair of the State Planning Commission, served as the session’s moderator and started off the discussion by noting that the surge in demand for warehouse space is creating a host of problems that have caught state and local leaders off guard: unanticipated demands on transportation facilities, loss of farmland, and disruptions to urban areas, among other concerns that land-use decision-makers are confronting.

The big news to come out of the session is that the Office of Planning Advocacy (OPA), which serves as the staff for the State Planning Commission, has issued guidance (viewable on their website under the heading “Reference Materials”) that is designed to help local leaders better understand the goods movement industry so they can make more informed decisions about where to site warehousing facilities. Donna Rendeiro, the executive director of OPA, provided an overview of the guidance and discussed how OPA can assist local decision makers with updating their planning and zoning to incorporate and reflect the information provided in the guidance.

Not all warehouse proposals have the same set of land-use and transportation needs or are appropriate for the same kinds of sites, a fact not well understood by local officials or residents who oppose warehouse development. To shed some light on how the industry works, Anne Strauss-Wieder, director of freight planning at the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, elaborated on the different types of warehouse buildings. Warehouses can range from the behemoths that receive goods coming off giant cargo ships and distribute them to smaller warehouses across the eastern half of the country to the local delivery centers from which the ubiquitous UPS or Amazon vans are dispatched to deposit packages at their final destinations, effectively performing the same role as local shopping centers but without the inbound car traffic.

Strauss-Wieder also touched on the types of vehicles that the different types of facilities tend to attract, an important consideration as to where a given facility might best be located relative to the transportation network. The OPA guidance has a section devoted to the hierarchy of buildings involved in goods movement and storage.

The larger facilities that are involved in wide-scale distribution of entire shiploads of goods tend to want to locate as close to the port as possible. But the older urban centers that surround the major port facilities in Elizabeth, Newark, and Bayonne are often also home to “overburdened communities,” neighborhoods characterized by high percentages of people of color or lower-income households. Because many of these neighborhoods have historically experienced a variety of environmental stressors, the legacy of New Jersey’s industrial past, the pollution emitted by the steady stream of trucks accessing the warehouses can represent a much more significant cumulative impact here than elsewhere. The OPA guidance has a section on air quality and health impact considerations, to draw attention to these cumulative impacts and recommend against locating certain kinds of goods-movement facilities in these neighborhoods.

This is not to say that warehouse development cannot offer positive outcomes to urban communities, however. Wilda Diaz, former mayor of Perth Amboy, described how a warehouse proposal provided her city with the opportunity to clean up a contaminated site formerly occupied by an abandoned steel mill. As part of a comprehensive agreement with the City that included numerous improvements (e.g. roads, stormwater infrastructure, implementation of green and sustainable initiatives), the warehouse developer mitigated the environmental hazards on the property, turning a polluted eyesore into a new source of tax revenue for the city and a source of employment for nearby residents–an important benefit for the municipality with the highest unemployment rate in Middlesex County. What’s more, the developer’s improved connections to the local street network enable some local residents to walk to work—especially important in a place where many households can’t afford cars—while allowing trucks to access the regional highway network in the other direction without having to travel on local streets. Diaz explained that communicating the potential benefits of the project via a public outreach campaign was important in overcoming negative perceptions, and that negotiating the benefits agreement with the developer was key to getting buy-in from the surrounding community.

Warehouses pose a different set of problems in more outlying locations. Julia Somers, executive director of the New Jersey Highlands Coalition, mentioned the risk of paving over important groundwater recharge areas in the Highlands, which are traversed by Interstates 78 and 80, two of the major arteries feeding into the port areas in North Jersey. The stretches of Warren and Hunterdon counties along I-78 are also home to some of the state’s prime farmlands, which can also be attractive to warehouse development because of proximity to the highways and lower land prices than at closer-in locations. New Jersey is a leading nationwide producer of certain fruit and vegetable crops, so when agriculture and warehousing compete for the same land parcels, it sets up a conflict between two industries of statewide importance, a conflict that may not be optimally resolved by leaving the decision to the local unit of government.

Warren County commissioner Jim Kern, as both a former mayor and now a county official, spoke to the need for regional coordination. He talked about New Jersey’s “home rule” system that invests municipal governments with power over land-use decisions and how the promise of property-tax revenue often leads towns to court development that may have negative effects on the environment or local quality of life, both within the host municipality and in surrounding jurisdictions. Somers pointed out that in other cases municipalities zone land for industrial use as a sort of placeholder, mainly to prevent it from being developed as housing, and are unprepared when a commercial developer proposes to actually build a warehouse on it, an example of the “be careful what you wish for” phenomenon.

As an example of what higher levels of government can bring to the table, Kern cited a Light Industrial Site Assessment that Warren County completed in 2020 that provided an overview of sites in the county that were zoned for warehousing and illustrated how many such sites were located next to roads that were not up to the task of accommodating truck traffic. In urban areas, concerns focus on trucks passing through residential neighborhoods while in rural areas the issue is two-lane roads that were not built to handle big trucks, but both situations illustrate the need to consider transportation networks when siting warehouses, which local governments may not be best equipped to do. The OPA guidance has a section intended to educate local officials about this issue.

In general, the OPA guidance is designed to offer a statewide perspective on warehousing, covering a broad set of issues. In the coming months, New Jersey Future will be reviewing the guidance and looking for ways that it can be institutionalized in state agency policies and practices, and we will be exploring the potential of its proposal for county-level technical advisory committees as a vehicle for bringing together the perspectives of multiple stakeholders as inputs into the warehouse siting process. We applaud the OPA guidance as a critical step toward a more systematic approach to accommodating growth in one of the state’s key industries.

Walking the Talk: Planning for Places that Actualize Equity and Inclusion

July 8th, 2022 by Kimberley Irby

“In this era of racial reckoning, especially triggered by the murder of George Floyd, we have to pause and ask what our role is as a profession, what responsibility we have had in creating the societies in which we live, and how we rectify [problems] with an equity lens,” stated Eleanor Sharpe, deputy director for planning and zoning in the City of Philadelphia, a panelist in the first plenary session of the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, hosted by New Jersey Future and and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association.

“In this era of racial reckoning, especially triggered by the murder of George Floyd, we have to pause and ask what our role is as a profession, what responsibility we have had in creating the societies in which we live, and how we rectify [problems] with an equity lens,” stated Eleanor Sharpe, deputy director for planning and zoning in the City of Philadelphia, a panelist in the first plenary session of the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, hosted by New Jersey Future and and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association.

The virtual plenary, titled Walking the Talk: Planning for Places that Actualize Equity and Inclusion, served as a follow-up to the previous year’s plenary called the Geography of Equity and Inclusion, which covered a big picture view of spatial segregation in the nation and in New Jersey specifically, as well as how we could mitigate it. The goal for this year’s plenary was to clarify what the planning and redevelopment community can and should do to achieve equity and inclusion in our communities.

The panel, moderated by Zunilda Rodriguez, senior associate at Nishuane Group, featured four distinguished speakers, including Sharpe; Maritza E. Mercado Pechin, deputy director of the Office of Equitable Development in the City of Richmond, VA; April de Simone, principal at Trahan Architects and co-founder of designing the WE; and Allison Ladd, deputy mayor and director of the Department of Economic and Housing Development in the City of Newark. During this plenary, speakers emphasized the importance of building trust with historically marginalized communities and establishing a robust process for their involvement throughout the stages of development or redevelopment, from planning to implementation.

How can we support accountability and transparency at the local level?

In response to this first question posed by Rodriugez, Mercado Pechin offered an example from the City of Richmond, citing a transportation policy guide that shared the blunt history of inequitable transportation projects, and thus, set the stage for choosing projects that could help remedy past mistakes. Later on, Pechin highlighted the legitimate concern of displacement from a project that will reconnect a community previously severed by a highway, and said that her office is examining solutions, such as ensuring there are more homeownership opportunities.

De Simone, a New York-based architect who co-led a national exhibit project called Undesign the Redline, reinforced the point that understanding historical context is necessary to avoid perpetuating inequitable outcomes, especially through projects that aim to undo the mistakes of the past, like highway capping. She reminded us not to assume that “just because we see development happening [in historically marginalized communities]… that the systemic conditions of inequity and disparities of poverty, health, and wealth-building opportunities are solved.”

How can we begin to rebuild trust with communities that have been left behind with empty promises for decades?

Several speakers brought up the challenges of building trust with the community and the audience asked for suggestions to tackle them. Sharpe, with the City of Philadelphia, urged planners to “listen more and talk less” when engaging with the public, noting that just hearing and acknowledging people is half of the work. Beyond this, Ladd, with the City of Newark, underscored the ability to adapt based on what the community is saying, as well as the need to be consistent with execution (i.e., following through on what one says they’re going to do). Ladd also acknowledged that “sometimes the listening and hearing parts are challenging, but we have to hear it even when it’s aggressive or uncomfortable, because that friction is actually where change happens.”

How can we thread equity and inclusion into local planning and/or processes?

Throughout the discussion, panelists echoed Sharpe’s saying, “slower is faster,” emphasizing that good community engagement requires time and deliberate, intentional focus. Sharpe also illustrated that effective engagement can empower communities to have a meaningful role in the creation of projects that will affect them. For example, she referred to the creation of Philadelphia’s Citizens Planning Institute, which educates cohorts of residents on planning and zoning, enabling them to translate technical aspects of government projects to their neighbors and assuage their concerns.

Additionally, Mercado Pechin shared that the City of Richmond used a similar community ambassador mechanism during their master plan process. All panelists agreed on the importance of compensating community volunteers for their time, both to ensure a socioeconomically diverse group and to affirm that insights from their lived experiences are just as valuable as the work they pay consultants to do.

To ensure equity and inclusion in community redevelopment, the panelists suggested that we intentionally engage in a way that brings different people to the table, especially those who have been historically left out. Though this can be challenging when trust is lacking, it is critical to build, or rebuild, a mutually beneficial relationship. Sharpe continually emphasized we are all learning and that there is no easy answer or silver bullet. Nevertheless, Sharpe reminded us that, “These are exciting times. There is a lot of opportunity as the world is shifting and changing, and our profession can show up and make our mark.”

Equitable, Sustainable Development and Redevelopment for a Bright New Jersey Future

July 8th, 2022 by Michael Atkins

Throughout the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, co hosts New Jersey Future and the New Jersey Chapter of the American Planning Association sought to convene panels featuring industry experts and community leaders. As one would expect with a “redevelopment” conference, themes of successful and sustainable redevelopment were highlighted in depth, while experts also attempted to educate attendees on diversity and inclusivity practices when developing housing and commercial spaces aimed at improving the lives of New Jersey residents.

“Redevelopment: Solving the Problems of Today, Creating the Community of Tomorrow,” specifically examined the vast opportunity for redevelopment to serve as a tool in addressing current problems within our built environment. Panelists included: Valerie Jackson, director Economic Development with the City of Plainfield; Tanya Marione, director of Planning for Jersey City; Jennifer Credidio of McManimon, Scotland, & Baumann; and Jessica Caldwell, founder of J. Caldwell & Associates.

Breakout session “Redevelopment: Solving the Problems of Today, Creating the Community of Tomorrow” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

New Jersey’s redevelopment law provides local governments with enhanced planning, zoning, contract and financial powers. These powers can produce economic value where the private markets cannot, and enhance municipal control over design, development, and implementation. Some of these economic incentives for redevelopment include: long-term tax exemption, grants or loans in aid of redevelopment projects, land acquisition and condemnation, redevelopment area financing, and developer eligibility for state incentives.

“Land is limited, so you have to be very strategic about redevelopment and land use,” said Valerie Jackson of Plainfield. Panelists brought case studies from their respective New Jersey cities and towns where redevelopment has afforded them the latitude to exert control in reinvigorating their communities. Examples include a shopping center that now lack the grocery store that once anchored the center, an abandoned quarry, a former hospital, and town centers in need of new investment and enterprise. Jersey City has a major redevelopment in the works. The City plans to redevelop and infill the former Honeywell industrial site and implement the City’s first new neighborhood in decades. The site promises thousands of units and 35% affordable housing, which will make it the largest mixed-income community in the tri-state area.

While redevelopment affords cities great control in encouraging redevelopment to vacant, abandoned, or underutilized lands, this reveals a broader question of how to foster diversity, equity, and inclusion within development projects and firms. This question was addressed head on at “Developers and DEI: Overcoming the Obstacles.” This panel featured developers Adenah Bayoh and Patrick Terborg; Eileen Della Volle, vice president of business development at KS Engineers; Attorney Jong Sook Nee, and Ron Scott Bay, chairman of Planning Board of Plainfield, NJ.

Breakout session “Developers and DEI: Overcoming the Obstacles” during the New Jersey Future and APA-NJ New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference 2022 at the Hyatt Regency, New Brunswick on June 16, 2022. Photo Credit: Keith Muccilli

The panelists broadly agreed that developers must embrace the changing landscape that has more heavily emphasized diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). Failure to do so results in missed opportunities, underserved communities, and money left on the table that developers would have otherwise capitalized upon with an integrated approach to building to community needs. Patrick Terborg punctuated this point succinctly, “you can make money by embracing diversity.”

Adenah Bayoh shared, “People are sometimes trying to be invisible, which doesn’t mean they have no rights.” She added that experience and representation matters on a given developer’s team as they seek to construct diverse and/or mixed-use communities, including adding a member of the community to the project team to inform project goals and implementation. Eileen Della Volle concurred, underscoring the importance of diversity by adding, “People may be diverse because of their experiences, and that is a valuable contribution, too.”

Ron Scott Bay further encouraged developers to open up to community inputs by imploring developers to “be open-minded” and acknowledge that “everyone should have an opportunity, not just a select few” with respect to serving on developer teams or living in newly constructed housing units. Patrick Terborg encouraged developers to “be intentional” when considering hiring and soliciting community input for development projects. Encouraging audience members to consider “who you can use that would add value and may be of color.”

In conclusion the panelists encouraged developers in the audience to embrace DEI by valuing team inputs and taking continual stock that DEI principles. Opportunities to embrace DEI include during hiring and promotion, project inputs, training and education of staff members and consultants, sourcing goods and services for a development project, and, importantly, conducting true outreach and emphasizing mutual understanding between developers and the communities they work with.

Constructing Accessible and Inclusive Communities for People with Disabilities

July 8th, 2022 by Hannah Reynolds

“Inclusion means different things for different people,” stated Carleton Montgomery, Executive Director of the Pinelands Preservation Alliance. “[With] the vast demand for accessible nature, [people are looking for] inclusion, not just being out in nature. That might mean a stable trail, being able to paddle…,” continued Montgomery as a panelist at the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference (NJPRC), sponsored by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association.

“Inclusion means different things for different people,” stated Carleton Montgomery, Executive Director of the Pinelands Preservation Alliance. “[With] the vast demand for accessible nature, [people are looking for] inclusion, not just being out in nature. That might mean a stable trail, being able to paddle…,” continued Montgomery as a panelist at the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference (NJPRC), sponsored by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association.

While an estimated 13% of people from South Jersey have a disability, Montgomery acknowledged that with friends, loved ones, and caregivers of New Jerseyans with disabilities, as much as half of the population might be affected by the inaccessibility of nature. By fostering inclusive use of the Pinelands through both the construction of secure trails and the creation of guided tours and paddling trips accessible to people with mobility-related disabilities, Montgomery and the Pinelands Preservation Alliance seek to encourage all New Jerseyans to care about and protect the region.

The virtual breakout session at which Montgomery spoke, titled Building Healthy and Equitable Communities Through Inclusion of People with Disabilities, was facilitated by Peri Nearon—Executive Director of the Division of Disability Services in the New Jersey Department of Human Services—on Wednesday, June 15. The event featured four engaging speakers, including Montgomery; Patricia High, Assistant Public Health Coordinator of the Ocean County Health Department; Lauren Skowronski, Program Director for Community Engagement at Sustainable Jersey; and Heather Cooper, MPA, Deputy Mayor of Evesham Township. Throughout the session, the speakers clearly articulated how imperative it is to uplift the needs and ideas of people with disabilities in their public planning work.

“Every public space should have easy public access. [We need to] care for all people in all places,” explained Heather Cooper, Deputy Mayor of Evesham Township. Cooper explained how in her role as deputy mayor, she had worked to foster inclusive participation of people with disabilities in town boards and programs; administered community surveys on accessibility; engaged town employees, citizens, and affiliates in educational efforts on access and inclusion; and sought to offer competitive employment opportunities for people with disabilities in Evesham Township.

Lauren Skowronski of Sustainable Jersey echoed the sentiments shared by Cooper and Montgomery about equitable access to public spaces as a means of connecting people with disabilities within the communities in the face of isolation. “We [put] policies and strategies in place to ensure that public facilities are built beyond the code requirements for true accessibility… When the municipality is notified public spaces are not accessible, they acknowledge and take action [to make these spaces more inclusive]… [In making these decisions], we need to engage the opinions of all residents [for] better involvement in municipal decision making.”

What might these accessible, inclusive public spaces look like? Patricia High of the Ocean County Health Department offered an answer. In her presentation, High shared about Tom River’s Field of Dreams, a 100% Americans with Disability Act (ADA)-compliant facility in Ocean County. The Field of Dreams was a garden with a wheelchair-accessible trampoline, zipline, and mini golf; a quiet corner for people with autism and other diverse needs; and a range of other accessible and inclusive features. High explained that the garden was created as an attempt to establish “inclusive gardening for all, cultivating health for all.”

Ultimately, the Building Healthy and Equitable Communities Through Inclusion of People with Disabilities panel at the NJPRC offered an opportunity to engage with equity and inclusion from a perspective that is too often neglected in public planning and redevelopment efforts, by planning and developing public spaces to specifically cater to the needs of New Jerseyans with disabilities. Parks accessibility is a crucial ingredient in fostering a strong connection between New Jerseyans and public spaces in their communities. By designing spaces to include persons with disabilities, developers, planners, business owners, and municipal leaders can expand the number of individuals that visit these spaces, whether more natural spaces like the Pinelands or more constructed spaces like the Field of Dreams farm. During the session, the panelists demonstrated that by building inclusive communities for people with disabilities, these communities will be made more accessible and welcoming for all New Jerseyans.

Beyond Getting from A to B: Ensuring Safer and Fairer Ways to Move Around

July 8th, 2022 by Michael Atkins

Transportation emissions comprise over 40% of New Jersey’s total greenhouse gases (GHG). Expanding bus and rail transportation options beyond cars not only addresses reduction of GHGs, it also increases affordability and improves general public health by getting transit users to walk or bike to popular modes of mass transit. In encouraging further adoption of public transit, planners, transportation agencies, and civic leaders must establish safety and fairness in order to achieve less vehicle miles traveled (VMT) to meet our climate change goals and foster healthy, walkable communities throughout New Jersey.

Transportation emissions comprise over 40% of New Jersey’s total greenhouse gases (GHG). Expanding bus and rail transportation options beyond cars not only addresses reduction of GHGs, it also increases affordability and improves general public health by getting transit users to walk or bike to popular modes of mass transit. In encouraging further adoption of public transit, planners, transportation agencies, and civic leaders must establish safety and fairness in order to achieve less vehicle miles traveled (VMT) to meet our climate change goals and foster healthy, walkable communities throughout New Jersey.

A panel titled “Beyond Getting from A to B: Ensuring Safer and Fairer Ways to Move Around” addressed just these intersecting issues at the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference (NJPRC), sponsored by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association.

Transportation today showcases a number of inequities in our built environment ranging from air quality to accessibility. Historically, federal funding and state departments of transportation (DOTs) have measured successful projects by vehicle speeds, which has incentivized the erection of freeways and their widening to attempt to alleviate congestion. This emphasis also encourages even persons of limited means in our society to consider the world as car-centric. Now, a shift in attitudes has led transportation professionals and officials to prioritize multi-modal and public transportation options, in order to ensure safety and equity to increase transit ridership, thereby reducing VMTs.

Panelists brought a broad range of experiences to the discussion, and an even greater depth of on-the-ground experience. They included: moderator Renae Reynolds, Executive Director of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign; Regan Patterson, PhD, Transportation Equity Research Fellow with the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation; Richard Ezike, PhD, Director of Infrastructure and Planning at CHPlanning Limited; Shawn Wilson, PhD, Secretary of the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development and President of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO); and Yolanda Takesian, Principal Planner of Kittelson & Associates.

In his keynote remarks, panelist Dr. Shawn Wilson conceded there is ample room for improvement within the transit sector. “The development of the transportation system has historically prioritized highways and focused on a limited range of users. That’s just the history of where we are.” Wilson reported that AASHTO’s Board of Directors passed a unanimous declaration in 2020 acknowledging the inequities of the past, and the negative impacts these transportation priorities have disproportionately affected Black and Brown communities. “As the state DOT community, we are committed to serve as stewards of an integrated, multi-modal transportation system that achieves economic, environmental, and social goals set by the representatives of the people we serve.”

Dr. Regan Patterson noted a disproportionate impact transportation inequality has on women, and the challenges they face in all modes of transportation. “Gender is as important as a disparity as race. Women are predominantly the caregivers of their family, so if the primary person needing care is in a wheelchair or is a child, is the sidewalk safe for their usage? Do women feel safe when walking or riding public transportation?”

“The most unsafe place for a pedestrian to be is within the vicinity of a bus stop,” warned paneliest Yolanda Takesian. “Adding a safety metric is crucial,” she added while highlighting the impacts of Vision Zero and Complete Streets programs across American cities to transform urban arterials – where jobs, restaurants, and retail stores often cluster – into safe pedestrian corridors, with protected bike lanes, and frequent bus service.

Takesian emphasized the importance of community conversations in building popular support behind these streetscape adjustments and encouraged community leaders and engineers to make the time to develop personal connections with the corridors they plan and redesign. “We need to recognize the value of lived experience” in reimagining our transportation system.

Dr. Richard Ezike built upon this prescription, suggesting the key to success is to ensure that “the community feels like they are being listened to and being heard and have a say in actual development.” Ezike supported the idea that the adjustment away from speeds is improving safety and access throughout the transportation system. Ezike also noted that “workforce development builds equity” and that hiring practices in resurfacing and redesigning streets to be people-oriented is a major opportunity to train and employ members of underserved communities.

Dr. Patterson pointed to consistent community organizing around environmental justice that has built energy behind audacious adjustments, such as highway removal in the states of California and Washington, and the allocation of Federal funding to address these issues throughout the nation. Audience members demonstrated a particularly acute interest in urban highway removal and historic inequities with state DOTs and the Federal Highway (FHWA).

Dr. Wilson offered an important perspective to attendees and panelists interested in addressing safety and equity in adapting our sprawling transportation system to 21st century challenges. Wilson noted the tendency to scale projects too big (to attract more funding in transforming a corridor), or too small (to avoid controversy, or in the name of expediency.). “We scale [transit] projects to multi-billion dollar size that are unaffordable, or conduct spot improvement projects that address a collision hotspot but ignore corridor connectivity.” While transportation agencies, planners and the public agree that safety and access are primary objectives in updating our transportation infrastructure, it remains a long road to hoe to realize a more equitable and inclusive system. Reimagining our transportation system includes remaking our cities and towns to offer a plethora of transit options and for those options to be safe and inclusive for all types of riders. In doing so, we can reduce our harmful emissions while improving affordability and public health outcomes with a robust multi-modal transportation system.

Demonstration Projects: Seeing is Believing—Doing is Achieving

July 8th, 2022 by Patricia Dunkak

“Streets make-up up to 80% of every communities’ public space. What if we start to think of streets as places for people, as well as places to move and store cars?” Moderator Laura Torchio of NV5 asked viewers to consider streets as places during the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference. For large design projects that alter current transportation design and systems, oftentimes the largest obstacle is public resistance to change in current habits. The session, Demonstration Projects: Seeing is Believing – Doing is Achieving, explored how demonstration projects in three New Jersey municipalities can lead to long-term design solutions that reduce vehicle miles traveled, increase transportation options, promote economic growth through infrastructure investments, and create better public spaces for all users.

“Streets make-up up to 80% of every communities’ public space. What if we start to think of streets as places for people, as well as places to move and store cars?” Moderator Laura Torchio of NV5 asked viewers to consider streets as places during the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference. For large design projects that alter current transportation design and systems, oftentimes the largest obstacle is public resistance to change in current habits. The session, Demonstration Projects: Seeing is Believing – Doing is Achieving, explored how demonstration projects in three New Jersey municipalities can lead to long-term design solutions that reduce vehicle miles traveled, increase transportation options, promote economic growth through infrastructure investments, and create better public spaces for all users.

Demonstration projects are short-term, low-cost, temporary projects used to pilot long-term design solutions that can improve transportation options for all users and upgrade public spaces. This concept of “try before you buy” creates an opportunity for public participation in transportation projects, which can reduce resistance to new designs. Temporary projects are non-threatening to a community’s current system and habits, and often lead to permanent projects supported by the community. The breakout session panel explored case studies and examples of successful demonstration projects—also known as tactical urbanism—that created more complete streets designed for all pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers.

Public engagement assists planners in making informed decisions for complete streets projects. Keith Hamas of the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority explained how Keyport Borough in Monmouth County used a virtual video game style system that allowed for survey participants to rate their streets and provide feedback on bike networks, access to schools, and stormwater management. Feedback from this outreach plan led to a selection of a high profile location that would generate enthusiasm for walkers and cyclists, while addressing a safety issue that exemplifies a complete street design. Ultimately, this temporary bike lane improved accessibility and showcased the benefits of safe crossing trails and enhancing a public space for non-drivers.

Experimental Pop-Ups are a new initiative organized by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission to help communities plan and execute tactical urbanism, including bike lanes and traffic circles. Kendra Nelson of DVRPC highlighted various stakeholder groups that played a pivotal role in executing an Experimental Pop-Up plan in Collingswood. The township indicated interest in providing bike lanes to increase bike passing distance and reduce vehicle speed. The materials for this pop-up design only cost around $10,000, and displayed to Collingswood cyclists and drivers the benefits of what a similar long-term design project would look like.

West Orange is an example of how a demonstration project can generate community support for a long term complete streets design project. EZ Ride’s Lisa Lee informed participants of a bike lane project that garnered awareness and support among schools and community groups in West Orange. Feedback from this demonstration project proved that a bike lane would benefit not just cyclists, but community members of all ages. Through an innovative promotional campaign sharing messages stating “Share the Road” and township installed electric signs noting the change in traffic patterns, West Orange cyclists and drivers experienced a shift in how they viewed transportation options in their town. This gradual shift was non-threatening to the community, as it did not change their streets overnight. This low-cost, temporary bike lane helped stakeholders develop and create a long-term design based on community feedback. This short-term project’s success piloted a permanent bike lane for all users.

All panelists in this session emphasized the importance of public engagement during the demonstration project case studies described in New Jersey. The short-term, low-cost, temporary projects can be used as examples for long term design solutions that shift the makeup of public spaces. These types of projects that allow the community to test an idea before they invest can improve design elements based on public participation. Through collaborative demonstration projects, communities can shift perceptions on transportation and how a complete street should look. These projects can lead to more equitable downtown centers, increase transportation options, promote economic growth through infrastructure investments, and reduce vehicle miles traveled.

Reducing Rain’s Repercussions: Exploring the Potential for Green Infrastructure on Redevelopment Sites

July 8th, 2022 by Andrew Tabas

“The benefits of green infrastructure are boundless,” says Jennifer Gonzalez, Director of Environmental Services and Chief Sustainability Officer in Hoboken. Green infrastructure (practices like rain gardens, green roofs, and rain barrels that capture stormwater) can brighten towns through more beautiful streetscapes, reduced flooding, improved health of both people and ecosystems, and increased pollinator habitat. During the “From Impervious to Green: Green Infrastructure on Redevelopment Sites” session at the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, three stormwater experts joined Jennfer for an exploration of strategies to increase green infrastructure implementation across New Jersey.

“The benefits of green infrastructure are boundless,” says Jennifer Gonzalez, Director of Environmental Services and Chief Sustainability Officer in Hoboken. Green infrastructure (practices like rain gardens, green roofs, and rain barrels that capture stormwater) can brighten towns through more beautiful streetscapes, reduced flooding, improved health of both people and ecosystems, and increased pollinator habitat. During the “From Impervious to Green: Green Infrastructure on Redevelopment Sites” session at the 2022 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, three stormwater experts joined Jennfer for an exploration of strategies to increase green infrastructure implementation across New Jersey.

In Hoboken, street trees, rain gardens, and bike lanes make streets more welcoming to all road users while managing stormwater. Photo credit: Andrew Tabas

It is an exciting time for green infrastructure advocates in New Jersey because the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) is working on two key regulations. First, NJDEP is in the process of updating the Stormwater Management Rules. As Gabriel Mahon, bureau chief of the Bureau of New Jersey Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NJPDES) Stormwater Permitting and Water Quality Management in the NJDEP, explained, the current rules require the use of green infrastructure on new “major development” projects. Towns implement the rules through their Stormwater Control Ordinances. Municipalities should stay tuned for the New Jersey Protect Against Climate Threats (NJ PACT) regulations, which may update green infrastructure requirements.

Second, as Mahon explained, NJDEP is also updating the Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permit. The MS4 Permit determines the way in which towns convey rain from streets and buildings to nearby rivers. Municipalities should prepare for the release of the final draft 2023 MS4 Permit. The preliminary draft permit explored the new idea of requiring municipalities to develop Watershed Improvement Plans, which would be a tool for each town to determine the best way to improve its own water quality.

Patricia Lindsay-Harvey, Willingboro Municipal Utility Authority and Willingboro Green Team Chair, and Jeromie Lange, Director of Development, Active Acquisitions LLC, showed that environment advocates and real estate developers can find common ground on green infrastructure policy. “Not only is green infrastructure necessary, but it’s beautiful; it has a great impact on mental health,” emphasized Lindsay-Harvey. Lange also emphasized his desire to see more green infrastructure implementation in order to “mimic the natural hydrology.” From the developers’ perspective, consistency and a “common sense” application of regulations are critical.

On redevelopment sites, there are many “opportunities for innovation” according to Lange. Mahon of the NJDEP explained that redevelopment projects can count as “major development” under the current Stormwater Management Rules, and that the requirements for these sites depend on the project size and whether there is a net increase in impervious surface. Implementing green infrastructure on redevelopment sites is essential to improving water quality across the state in the long term. In Hoboken, Director of Environmental Services Gonzalez added, the Citywas able to complete a redevelopment project at 7th St. and Jackson St. that managed stormwater above- and below-ground, while providing new community spaces.

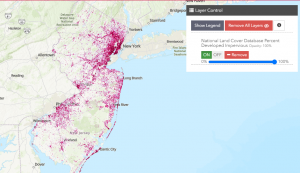

All four speakers agreed that it will be essential to manage the stormwater generated by the state’s roads and bridges through the implementation of Complete and Green Streets. This is important because streets contribute to NJ’s overall impervious surface (see below). The New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) should step up its development of Complete and Green Streets on state-owned roads and should steer funding toward local projects that incorporate green infrastructure, sidewalks, wheelchair accessibility features, and bike lanes.

Roads, bridges, and roofs are all examples of impervious surfaces. This map shows the distribution of impervious surfaces in New Jersey. The dark red areas have more impervious surfaces than the lighter areas. Photo credit: New Jersey Water Risk and Equity Map; data from the Multi Resolution Land Characteristics Consortium.

Stormwater utilities (a dedicated funding mechanism for stormwater management in which users are charged a fee based on impervious cover) are one potential tool to incentivize the use of green infrastructure including, as several panelists highlighted, on state-owned streets. The four panelists agreed that effective and well-managed stormwater utilities are essential to promoting green infrastructure across New Jersey.

There are many ways for residents to get involved in the journey of mainstreaming green infrastructure across New Jersey. These include joining the local green team, building a rain garden, motivating students to build green infrastructure at their school, commenting on site plans to support developers who use green infrastructure, and becoming a Green Infrastructure Champion. As Jennifer Gonzalez of Hoboken said, “we are all in this together,” so start your green infrastructure journey today!