Older Homeowners in Car-Dependent Suburbs Face a Reckoning

Author: Tim Evans

February 2021

Arthur Nelson at the University of Arizona recently released a study, which he calls “The Great Senior Short Sale,” noting a mismatch between the number of retired or soon-to-be-retiring Baby Boomers who over the next decade or two will be seeking to sell their (mostly single-family detached) homes and the much smaller number of younger homebuyers who might be interested in buying those homes. The study predicts that “many baby boomers and members of Generation X will struggle to sell their homes as they become empty nesters and singles. The problem is that millions of millennials and members of Generation Z may not be able to afford those homes, or they may not want them, opting for smaller homes in walkable communities instead of distant suburbs.” Nelson estimates that by 2038, the supply of single-family homes on large lots could exceed demand by as many as 18 million homes nationwide.

New Jersey Future has called attention to a different, but related, mismatch in our 2014 report Creating Places To Age in New Jersey, which notes that there were hundreds of thousands of older residents who were “aging in place” in places that were designed for travel almost exclusively by automobile, creating a looming problem for older people who may soon be looking to scale back their driving, or may be forced to give it up altogether.

We have also documented, in our 2017 report Where Are We Going? Implications of Recent Demographic Trends in New Jersey, that Millennials1 are indeed drawn to compact, walkable places where they don’t need a car every time they leave home. And they don’t want to live in car-dependent suburban sprawl, where options other than single-family detached homes are in short supply.

Stranded in Car-Dependent Neighborhoods

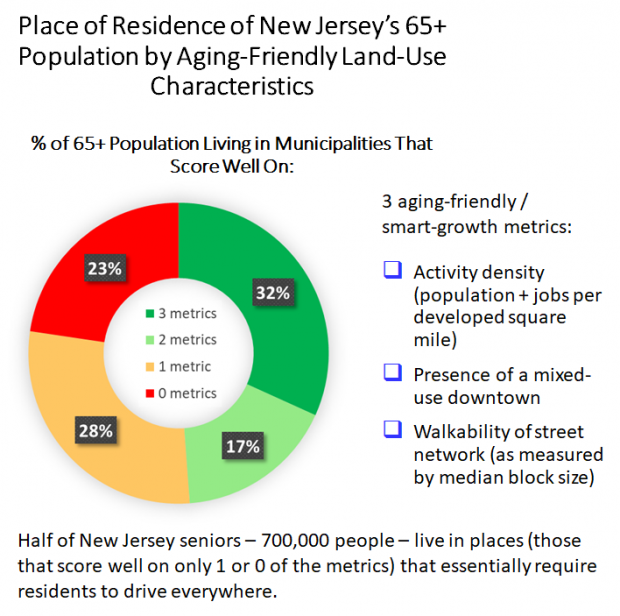

Seven years later, it is worth revisiting the question of how many New Jersey seniors might soon find themselves stranded in car-dependent neighborhoods. As of the 2018 five-year American Community Survey, there are about 1.38 million New Jersey residents age 65 or older, making up 15.5% of the state’s population. Slightly more than half of them (51.2%) live in municipalities that score well on only one (28.5%) or none (22.7%) of New Jersey Future’s three smart-growth metrics2—net activity density (people + jobs per developed square mile), presence of a mixed-use downtown, and median block size (a measure of street network walkability)—that are designed to identify compact, walkable centers. This represents just over 700,000 seniors living in places that do not lend themselves to aging in place, in terms of being able to accomplish daily activities without having to drive everywhere.

Meanwhile, only 40% of young adults (age 22 to 34) live in these same low-scoring places. This is an even smaller share than the 46.1% of young adults who lived in similarly low-scoring places in 2013. Instead, younger generations are drawn to live-work-shop-play environments where they don’t need a car every time they leave the house, and are increasingly avoiding the more car-dependent places where a majority of the state’s older residents live.

The wave of retiring Baby Boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) has not crested yet. The oldest Boomers are now 74 years old, but the youngest are still only 56. And the younger Boomers are just as concentrated in car-dependent places as are the older half of their generation: the share of people age 55 to 64 (as of the 2018 ACS) living in municipalities that score well on only one or none of the smart-growth metrics is 51.3% nearly identical to the percentage for the 65+ population. So the problem of older residents living in places that are not conducive to aging in place is going to continue to get worse in the near future, as the rest of the Baby Boom ages into retirement.

Difficulty Downsizing

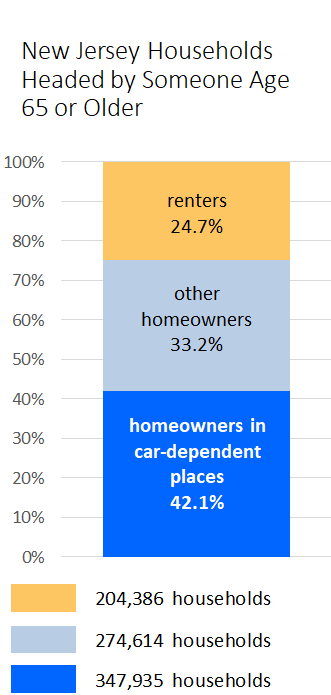

The Arthur Nelson study looks specifically at older residents who own their homes, since these households face the issue of needing to sell their homes before moving to a more aging-friendly location, rather than simply declining to renew a lease. In New Jersey, there are an estimated 826,935 households headed by someone age 65 or older, of which 75.3% percent are homeowners. Of these 622,549 senior homeowner households, more than half— – 55.9% percent, or 347,935 households— – live in municipalities that score well on only one or none of the three smart-growth metrics. To give an idea of the scope of the coming problem, these senior-headed households who own homes in car-dependent places that are not in demand among younger generations of potential homebuyers actually represent more than one in ten (10.8%) of all households in the state.

Many of these older homeowners will be looking to downsize as they age. Statewide, 85.7% of homeowners age 65 or older live in a single-family home.3 In 236 of the state’s 565 municipalities, the percentage is greater than 95%. In contrast, among households headed by someone 65 or older who are renting their home, only 14.7% are renting a single-family home, whether detached or attached. The quarter of senior-headed households who are renters have generally already downsized.

Downsizing while remaining in town may prove difficult for many older homeowners. In many of the car-dependent places where seniors are overrepresented, smaller housing unit types that are more conducive to aging in place are generally harder to come by. In the 340 municipalities that score well on either zero or one of the smart-growth metrics—and which are home to more than half of the state’s 65+ residents—single-family detached homes make up 70.7% of the collective housing stock, compared to only 53.6% statewide, and to only 29.9% of the total in the 119 most aging-friendly municipalities, the ones that score well on all three metrics. The places with the least diverse housing supplies also tend to be among the most car-dependent, two factors that both work against aging in place for the large number of 65+ residents who live there.

Becoming More Aging-Friendly

What can a community do to make itself a better place in which to grow older? New Jersey Future’s recently published guide Creating Great Place to Age in New Jersey: A Community Guide to Implementing Aging-Friendly Land Use Decisions cites four land-use characteristics that make a place conducive to aging in place: a mixed-use downtown or “center”; a variety of housing options; safe and accessible transportation; and accessible public spaces and amenities. The guide offers advice on how to foster those characteristics. The most effective solutions will vary by town, depending on which of these characteristics each place most needs to improve upon.

An important step that just about any municipality can pursue is to diversify its housing stock to create more of the kinds of homes that downsizing seniors (and young adults!) are likely to be looking for. Most municipalities, even those that are mostly built-out, can look for opportunities for infill development, especially on surface parking lots, which can be viewed as a sort of “land bank” in places where undeveloped land is running out. To allow developers to capitalize on such opportunities, municipalities should make sure their zoning codes are updated to allow “missing middle” housing types like duplexes,

3- and 4-plexes, small apartment buildings, and accessory dwelling units that can add housing density while visually blending in with existing buildings.

New Jersey Future’s recent report Municipal Strategies to Diversify Housing Stock For An Aging Population: A Case Study Report offers a number of strategies for creating a wider range of housing types. It also presents case studies as examples of where some of these strategies have been successfully implemented, including accessory dwelling units, form-based code ordinances (which rely on regulating the mass and bulk of buildings rather than their use type or occupancy), transit-oriented development (TOD) overlay zones, public-private partnerships in the conversion of a non-residential building to residential use, and modular, movable “tiny homes.”

Another step that municipalities of all stripes can take is to improve the pedestrian environment. Places that already have a mixed-use, compact development pattern can make sure sidewalks are kept in a state of good repair, provide public seating opportunities (street benches, public plazas, etc.), and make it safer to cross the street with traffic-calming measures like raised crosswalks, curb bump-outs, or modified traffic-signal timing. Places that are more car-oriented can use redevelopment and infill projects as an opportunity to add sidewalks where they don’t exist, reduce the number of curb cuts so as to reduce conflicts between vehicles and pedestrians, put parking behind buildings rather than in front, and add urban open spaces.

Geographically larger townships with spread-out development or undeveloped land surrounding one or more small centers can choose to actively steer new development into those existing nodes; examples include Mullica Hill in Harrison Township and Williamstown in Monroe Township, both in Gloucester County; New Gretna in Bass River Township, Burlington County; Lawrenceville in Lawrence Township, Mercer County; Kingston, which straddles South Brunswick Township in Middlesex County and Franklin Township in Somerset County; or the downtowns of Hammonton, Cranbury, Bernardsville, and Sparta.

Places that are built-out but with a more spread-out, car-dependent development pattern face perhaps the biggest challenge. With their car-oriented, branching street networks largely fixed in place, their ability to make themselves more aging-friendly will likely need to focus on retrofitting larger development parcels like obsolete office parks or aging malls and strip shopping centers. For example, Somerdale and Voorhees have both attempted to refashion shopping centers (an outdoor strip center in the former case, an enclosed mall in the latter) into mixed-use centers by constructing new buildings – including housing – on surface parking lots and adding pedestrian connections and amenities. In Parsippany, a developer has demolished a defunct office complex and is replacing it with a mixed-use project involving apartments and street-facing retail.

Given that these more spread-out places also tend to be dominated by single-family detached homes, their options for diversifying the housing stock should include not only accessory dwelling units like in-law suites or over-garage apartments but also the conversion of single-family homes to multi-family dwellings as demand for large single-family units wanes.

1 The beginning and ending years for the Millennial generation vary depending on which demographer you ask. The Pew Research Center has decided on a definition including anyone born from 1981 through 1996, as have the Brookings Institution and the Federal Reserve Board, according to Wikipedia. The Arthur Nelson study uses birth years from 1981 through 1997. New Jersey Future’s 2017 analysis used 1980 through 2000 as a rough definition to guide the choice of Census Bureau age ranges to use to represent the generation.

2 These metrics are an update of a set of metrics originally developed in New Jersey Future’s report Creating Places To Age in New Jersey to measure a municipality’s aging-friendliness from a land-use perspective.

3 This includes both single-family detached units and single-family attached units (i.e. townhouses/rowhouses); American Community Survey cross-tabulation data broken out by age of householder do not distinguish between the two.