New Jersey Future Blog

Rethinking Colonial Narratives and Transforming Native Insight into Actions: Indigenous Preservation of History

July 20th, 2023 by Sneha Patel

“Lenape means ‘the original human’, and that is where we need to get back to,” Chief Vincent Mann expressed, adding, “[reconnecting with the land] would provide us a way to encourage the people of tomorrow to take what we are sacrificing to create for them to further the future.” Indigenous people have a rich history of interacting in harmony with the environment. Colonialism commodified nature and continues to overshadow the indigenous history that existed in the Hudson Bay, and severed modern society from the ways of life that sustained pre-colonial populations. Panelists at a session dedicated to the subject at the 2023 Planning and Redevelopment Conference suggested creating a cultural interpretation center that preserves native history, through immersive teaching and community formation, as the start of a new strategy in facing a changing climate, while providing historical context on the Hudson Bay estuary and its ecosystem.

Moderated by Nagisa Manabe, Director of Development, Ramapough Culture and Land Foundation. The 2023 Planning and Redevelopment Conference session “Challenge Established Colonial Narratives of this Region’s History and Transform How We Communicate and Preserve indigenous History” recollected the painful past of native people that lived in the Hudson Bay area, and the importance of rewriting colonial history to disclose indigenous truths. The speakers Kerry Hardy, Historian, Lead Researcher and Cartographer at the Public History Project; Jack Tchen, Professor and Director, Clement Price Institute of Rutgers University Newark; Vincent Mann, Chief, The Turtle Clan of the Ramapough Lenape Nation; discussed the important role New Jersey indigenous communities can play in our region’s development and ensuring a resilient and equitable New Jersey.

Kerry Hardy, Historian, Lead Researcher and Cartographer at the Public History Project, speaking about the Hudson Bay and oyster bank during the virtual session, Challenge Established Colonial Narratives of this Region’s History and Transform How We Communicate and Preserve indigenous History, at the 2023 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference.

The Hudson Bay area was a natural source for oyster, clam, fish, and waterfowl resources that provided enough protein to sustain humans through the winter season. Native groups, such as the Munsee/Mohican, Hackensack, Raritank, Assunpink, Lechauwitank, and Minisink, navigated the Minisink Path 100 miles or more to the mouth of the Hudson River. Cheesequake, at the mouth of the Hudson, became a mecca and gathering site for native populations, where ceremonial council fires were held. Today, massive shell deposits hint at Cheesequake being once a major social center in indigenous life.

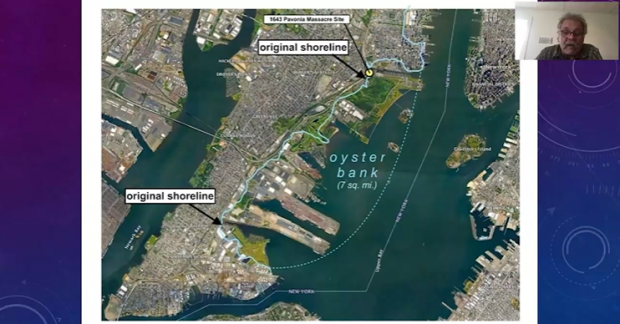

New Jersey’s estuary and tributary rivers, such as the Passaic and Hackensack River, previously held a seven mile wide oyster bank. Colonization spurred the conversion of wampum shells into currency for fur trade. Jack Tchen reflected “During this brief period of time we go from millennial uses of the bioregion as a cultural, food, and lifeways commons, to settler colonialism by turning natural resources of the region into a commodity marketplace.” Genocide and industrialization have left the original oyster bank largely devoid of natural resources and buried under a defunct railyard. Today, approximately half of the original oyster bank is covered by Liberty State Park.

Vincent Mann, Chief, The Turtle Clan of the Ramapough Lenape Nation, speaking during the 2023 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference with image of Liberty Park spanning approximately half of the original oyster bank.

Chief Mann remarked on the way that land and people hold the suffering of the violence that took place. The land that once forced migration of indigenous people became the entry point for millions of immigrants into the United States of America. “When you look at the Liberty State Park, it is not just the destruction you see, but the ability to replant the seed. To have that seed be something that can prosper and benefit all of humanity by telling the story of this land prior to contact, and telling the story of enslavement,” Chief Mann reflected.

Chief Mann proposes a cultural interpretive center to recount the history of America before it became the United States, suggesting the center would expose visitors to the parts of history that have been erased, and pave the way for an unprecedented reconnection to nature. Tchen explained the intimate knowledge of native people can demonstrate ways to work in harmony with nature to “rewild and protect the region, so that we have hope for the future and not have to build high walls to keep the ocean away or drain the rainstorms that are hitting us.”

Indigenous people, principally members of Lenni-Lenape tribes, are reasserting their ties to the environment, and reclaiming the shoreline to reseed oyster beds for future generations. “What you call climate change, I call human change,” Chief Mann expressed. He imagines the Liberty State Park interpretive center as a multicultural hub to preserve and spread knowledge about the proper way to treat nature, providing a travel destination for people to deeply interact with nature. He commented “we could create trail centers…, wild medicinal gardens, and ceremonial stone landscapes to educate people.” Knowledge would become a form of protection to keep hiking trails, like the Appalachian, untouched and clean.

“Colonialism isn’t just the domination of the Dutch or the British over the people…but it’s also about colonizing nature itself,” Tchen remarked. “This vision is also about how the park is a portal in which another way of life is revived.” Interpretive centers are crucial in showing what culture is still alive and showing the knowledge that the indigenous people have that has been recognized by scientists. While the world operates in colonial thought, Chief Mann believes that if they can collaborate with scientists on alternate opportunities that native people follow, they can inspire future generations to view nature differently. He explained, “we are planting the human seed of thought and all of those things need to be nurtured.” Chief Mann concluded the session with inspiring comments for the future. “The sun is always shining somewhere…There is always hope for tomorrow, and our hope is to see that in tomorrow’s people.”

Related Posts

Tags: climate change, community, cultural preservation, ecosystem, historic preservation, history, Indigenous people, native history, natural resources, preservation