New Jersey Future Blog

Sustainable and Cost-Efficient: Implementing a Dig-Once Policy in Trenton

August 30th, 2024 by Samirah Hussain

Lead service line replacement in Newark, New Jersey. Photo by the City of Newark.

Funding, funding, funding–the chorus frequently heard at the inception of almost every community improvement project. Financing remains one of the largest obstacles to infrastructure improvements. The increased frequency and severity of climate disasters and subsequent repair efforts have only exacerbated the issue. The solutions, however, lie in new and innovative approaches to infrastructure development—one such strategy being the dig-once policy.

A dig-once policy is a strategy to coordinate major community infrastructure projects to reduce negative environmental effects, construction disruptions, and costs. Some policies may focus on installing new, modernized infrastructure, such as telecommunications, during the excavation phase of major roadway or water projects. Others may focus on coordinating priorities of state agencies, such as the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), to align investments into major infrastructure improvement projects for mutual benefit. In the case of Trenton, New Jersey, the dig-once policy could serve as an example of a sustainable and cost-efficient method to install green infrastructure alongside the city’s lead service line replacement program.

Trenton: A Case Study

Background

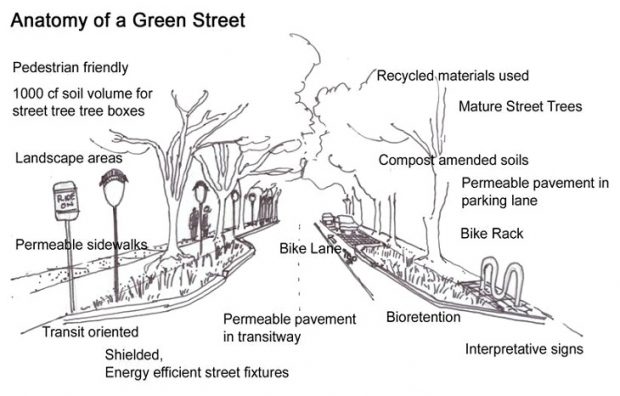

In 2022, the City of Trenton passed an ordinance to establish a Complete and Green Streets policy, which aims to create accessible and safe roads for bicyclists, public transit users, pedestrians, and drivers while incorporating green infrastructure to manage stormwater runoff, reduce air pollution, and more. Since then, the city implemented a wide variety of community engagement, construction, and research projects largely funded by state and federal grants to accomplish the goals in their adopted policy. At the same time, Trenton Water Works, a publicly owned drinking water system, is undertaking a lead service line replacement program in compliance with state legislation mandating the removal of all lead service lines statewide by 2031.

Courtesy of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

In both areas, Trenton has excelled. New Jersey Future’s Managing Green Infrastructure program conducted research to log Complete and Green Streets resolutions or ordinances passed in the Delaware River Basin, as well as Complete and Green Streets projects municipalities took on as a result. Based on this research, the city is one of the leading municipalities in the Delaware River Basin for Complete and Green Streets green infrastructure projects. Since 2017, Trenton Water Works reported that it has already replaced almost 30% of its lead service lines and is currently developing a plan to replace its remaining service lines by 2031.

Despite this success, more work can be done. Trenton Water Works reports it has replaced approximately 10,000 lead service lines already, and estimates there may be up to 20,000 still remaining. Complete streets, tree-lined roads, and rain gardens have been constructed in certain areas throughout Trenton. “Our Streets: A Bike Plan for All” is a community engagement and urban planning project carried out by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission and City of Trenton, has the goal of establishing complete streets all across Trenton. As of August 2024, the project is still developing its final report, highlighting that the work is nowhere near finished.

Implementing The Policy

Trenton is uniquely positioned to build on its success by implementing a dig-once policy while completing lead service line replacement and installing complete and green streets. Lead service line replacement requires digging up roads, lawns, and green spaces at multiple points in the removal process. Complete and Green Streets projects require repainting roads, installing safety equipment, planting trees and rain gardens, and extending roads. Implementing a dig-once policy would mean contractors for both projects align construction and contractors work collaboratively in the same locations. For example, as contractors dig up asphalt for lead service line replacement, infrastructure for green streets can be installed in the same areas. When the road is repaired and repaved, a complete streets design can be implemented. Having to “dig once” for two different projects saves on construction costs, limits construction disruptions and road closures, and reduces excessive environmental disruptions.

As the state’s capital, Trenton has both the visibility to garner public support for such projects and the duty to act as a role model for other municipalities. With climate-related disasters reaching an all-time high, investing in climate-resilient infrastructure is more pressing than ever.

The difficulty lies in achieving such a high level of coordination between organizations doing unrelated work but aiming for similar improvements to water quality and public safety: Trenton Water Works, the New Jersey Department of Transportation, and the City of Trenton. Technical assistance providers, like New Jersey Future, take the initiative to facilitate the required connections. Moreover, both lead service line replacement and Complete and Green Streets projects require oversight and involvement from overlapping intermediary organizations, like the NJDEP and the NJDOT. These state agencies can utilize their oversight to facilitate coordination between lead service line replacement and Complete and Green Streets projects. With state agencies and municipalities operating on limited budgets, fully funded by taxpayer dollars, coordinated planning on overlapping infrastructure initiatives is in the public’s best interest to save costs.

Closing

Collaboration has the power to make the dig-once policy a reality, saving time, money, and the environment all at once. In the vast majority of townships, the need for infrastructure improvements often exceeds the amount of funding available. Many projects, as is the case in Trenton, are funded with state and federal grants that are limited in quantity and require a township to dedicate additional resources just to apply. A lack of funding, however, does not cause community needs to disappear. Complete and Green Streets are necessary to create healthier, safer, and more comfortable communities resilient to worsening climate disasters. Lead service line replacement is vital to address the life-threatening effects of lead in our community’s drinking water. The dig-once policy offers a strategy to address Trenton’s community needs while saving money and resources. We must rely on innovative solutions to pave a path toward progress—and our state’s capital has the opportunity to lead the way.

Harmful Algal Blooms impacting recreation season for NJ Lakes

July 30th, 2024 by Chris Sotiro

Budd Lake, New Jersey’s largest natural freshwater body, was once an attractive vacation spot in North Jersey during the latter half of the 19th century for sunbathing, swimming, boating, and nearby attractions that have continued to today. Now, Budd Lake faces water quality impairments that threaten the recreation season and associated economic activities. Harmful algal blooms (HABs), caused by the overgrowth of cyanobacteria, have frequently shut down the lake for several weeks during peak summer months. Budd Lake is not just for boaters, anglers, and sportsmen; it serves a vital role in the watershed as the headwaters for the South Branch of the Raritan River, which supplies drinking water to over 1.8 million people living downstream. HABs degrade water quality to the point of toxicity, making this a matter of environmental concern and a public health dilemma. During severe bloom events, most water treatment facilities are not equipped to handle high levels of cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in source water, putting otherwise healthy residents at risk of adverse health effects.

Harmful Algal Blooms

Human activities enable and exacerbate cyanobacteria growth when favorable environmental conditions are met, such as extreme heat and low flow rates. When nearby residents spray hazardous fertilizers on their lawns or when cars leak oil and grease while passing through US Route 46, those non-point source pollutants can be carried into the lake via stormwater runoff, acting as nutrients for cyanobacteria. Two main sources of nutrients are nitrogen and phosphorus, which can originate from residential, agricultural, or industrial sites, all of which can be found in proximity to Budd Lake. This problem is not confined to Budd Lake alone; major lakes throughout the state have fallen victim to HABs and restricted recreation to protect public health. Spruce Run Recreation Area in Hunterdon County – the third largest reservoir in the state—has already banned swimming for the rest of the summer after a HAB was detected in early July. Once a bloom forms, the affected water can harm humans and disrupt aquatic ecosystems.

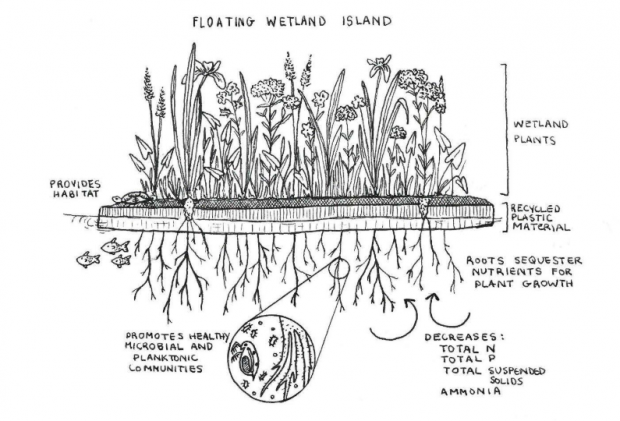

An example of a floating wetland island

Runoff from roadways and nearby neighborhoods is an issue that every municipality must grapple with. Existing gray infrastructure, such as traditional detention basins and pipes, are successful in redirecting stormwater, but fail to filter pollutants out of runoff or prevent contaminants from reaching nearby lakes and streams. While nonpoint source pollution is inevitable, whether or not those pollutants make it into water bodies is a question of effective stormwater planning. Green infrastructure is a low-cost, nature-based solution that sustainably improves water quality, absorbs greenhouse gas emissions, and provides new habitats for aquatic life. In the case of Budd Lake, floating wetlands are a form of green infrastructure that is being deployed to combat HABs by filtering nutrients from runoff that float at the water’s surface.

This illustration, sketched by Ivy Babson of Princeton Hydro, conveys the functionality of a floating wetland island.

Similar green infrastructure projects, such as rain gardens, porous pavement, and bioswales, can be retroactively installed on nearby properties to absorb stormwater and filter pollutants before they can discharge into Budd Lake. New Jersey Future’s Stormwater Retrofit Guide outlines best management practices for installing green infrastructure projects and methods to identify potential retrofit areas. This guide also showcases success stories of stormwater retrofit projects that have improved the health of watersheds throughout the State, such as those in Franklin and Lakewood Townships.

Stormwater basin retrofit in Franklin Township

Cleaning up Budd Lake will take years of collaborative, multi-agency effort. To combat HABs throughout the Garden State, $13.5 million in state and federal funding was made available for municipalities by Governor Murphy in 2019 for evaluation, treatment, prevention, and upgrades to sewer and stormwater systems. This funding, along with grant support from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), allowed the Raritan Headwaters Association, Rutgers Cooperative Extension Water Resource Program, and Mount Olive Township to draft a watershed restoration and protection plan. This plan will improve Budd Lake’s water quality by incorporating green infrastructure at strategic sites around the lake to capture and filter large volumes of stormwater runoff.

As HABs have been occurring more frequently in recent years due to overdevelopment and steadily increasing annual precipitation rates, there is a growing need to curtail the use of environmentally harmful products while implementing nature-based solutions to mitigate the discharge of pollutants into major water bodies. New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the country, making it highly susceptible to pollution from stormwater runoff around residential, industrial, and commercial development. As of January 1, 2023, every municipality in the State must comply with new updates to the MS4 Tier A Permit, including the requirement to develop a long-term Watershed Improvement Plan, which must be finalized by the end of 2027. As municipalities draft this Plan in the coming years, it is crucial to explore opportunities to incorporate green infrastructure as a preventative measure that can capture, absorb, and filter runoff to prevent the growth of HABs at beloved community recreation sites and to safeguard water quality.

Heat, Air Quality, and Hope: Community Research and Resilience in Elizabeth, NJ

July 30th, 2024 by Sabrina Rodriguez-Vicenty

Famartin, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsFamartin

Elizabeth is nestled on the shore of Newark Bay in Union County, a dense, urban enclave in the heart of the Meadowlands estuary and wetlands. Our neighbors include: the Newark Liberty International Airport, where planes fly by my apartment multiple times a day creating noise nuisance. The Port Newark–Elizabeth Marine Terminal, the third-busiest container port in North America, and principal facility for goods entering and leaving the Northeastern United States. The Bayway Refinery, a petrochemical complex in operation since 1908 that produces gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, propane, and heating oil. And Exit 13 of the NJ Turnpike, where every day a quarter of a million cars and trucks emit carbon dioxide and release tire particulate matter into the nearby community. Needless to say, Elizabeth has the qualifications to be classified as an environmental justice community by the EPA, and as one of the most polluted municipalities in the nation is recognized by the state as an environmentally overburdened community.

I was born and raised in Puerto Rico, a small Caribbean island rich in natural resources that suffers from environmental issues like flooding, hurricanes, heat islands, and lacks autonomy and representation, and therefore financial resources for disaster recovery and mitigation. Two years ago, I moved from Puerto Rico to Elizabeth, to attend Rutgers University to study public policy. When I opened my mailbox for the first time in my new home I was greeted by a startling welcome — I received a postcard for a class action lawsuit, which read: “If you’ve lived in Elizabeth or Linden for 10+ years, you may be eligible for compensation regarding environmental hazards.”

“Elizabeth, New Jersey was part of a nationwide study of five cities where all of the maps showed the same stories, that redline areas were prone to heat and flooding issues as well as air quality, which raised asthma rates and health conditions for its residents,” John Evangelista, Ground Works Elizabeth. As a minority woman of color, it seems that, at least for me, there is no escaping environmentally overburdened places to live, or is there?

The panelists of the 2024 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference session “Beating the Heat and Bad Air in Elizabeth, New Jersey” contributed a variety of experiences and deep firsthand knowledge that suggests there is reason for optimism. The session moderator was Clinton Andrews from Rutgers University, who led a community-based participatory research study funded by the National Science Foundation and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to better understand heat and pollution effects in Elizabeth. Other panelists included Carmen Rosario, a Master’s in City and Regional Planning student from the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Policy, and Jennifer Senick, Senior Executive Director of the Center for Urban Policy Research both at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, and Ground Works Elizabeth’s Deputy Director John Evangelista.

Rutgers’ research goal was to monitor the impact of heat exposure both outdoors and indoors in select Elizabeth Housing Authority (HACE) sites. Affordable housing locations include greater vulnerable populations like seniors and people with asthma, among residents with other health conditions. The study uses sensors and micronets to achieve a smart city paradigm that raises awareness to environmental stressors, enables greater community-level advocacy, and builds citizenship engagement. For the outdoor portion of the study, they installed sixteen sensors around HACE sites, a step that should be implemented in other EJ EPA communities. For the second portion of the study, connections were established between indoor and outdoor air quality using personal exposure measurement devices to identify how personally folks are exposed to environmental stressors, such as indoor smoking, cooking and cleaning choices, and (frighteningly) opening windows.

See page for author, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Key partners:

This research brought together two key partners. The Bloustein microclimate class helped in identifying, through geospatial analysis, community asset maps that included: hospitals, cooling stations, adult day centers, senior citizen centers, libraries, and food pantries. Students also identified policy adjustments for community health, and infrastructure focus to mitigate risks. The second partner was Groundwork Elizabeth, a community-based organization that has worked for over twelve years to develop public health and environmental programs for Elizabeth. Recently, Groundwork Elizabeth launched the Climate Safe Neighborhoods Initiative, a community-based task force advocating municipal policies to mitigate climate change impacts.

Lessons learned:

There were many various stakeholders in the project, each with their own needs. Researchers quickly identified the need to create a customized user experience for the community members. The project used community engagement in system design, including product design—hearing and listening sessions and brainstorming workshops—to answer varied demands. As Elizabeth has a predominantly Hispanic population, it was important to meet the community in their community centers, translate to Spanish, and provide multilingual engagement sessions. The student researchers and future planners learned the importance of conciseness when presenting findings by using relatable language. Another lesson learned is that developing connections and trust requires time. It is not possible to drop sensors into a community by parachute; Groundwork Elizabeth’s more than a decade of community involvement work, along with related relationships, all contributed to the project’s growth and development.

There are troubling connections between race-based housing segregation and climate change. Those who have contributed the least will pay the most. With increasing technological advances and accessibility to micronets and sensors, the hope is that this study is replicated in other environmentally overburdened communities. Although the model requires expertise, deep engagement, and grant support, it’s transferable and replicable across New Jersey and the nation. It is important to use socio-ecological systems framework to connect social and natural sciences; which can identify solutions to complex challenges like heat exposure and find diverse partners to solve them. It is imperative to continue research and present findings to communities that suffer from environmental hazards, so they can make informed decisions about their health.

New Jersey Needs More Housing, and Municipalities are on the Front Lines

July 30th, 2024 by Chris Sturm

Without a safe, stable place to call home, how can people achieve any personal goals?” asked Department of Community Affairs (DCA) Commissioner Jacquelyn Suárez. Her opening remarks kicked off the session, “Housing: What’s Next in New Jersey?” at the 2024 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference. Suárez described the agency’s “housing first” model, including programs to facilitate home ownership, prevent homelessness and support walkable downtowns.

Four panelists joined Suárez to discuss solutions to the housing crisis, which affects people of all races and many incomes. Poverty is statewide, explained Peter Rosario, President and Chief Executive Officer at La Casa de Don Pedro, citing applications from mostly white families for free and reduced school lunches in suburban Toms River. But he added, “the biggest density problem in this state is single-family homes, which are weaponized against black and brown communities.”

“Traditional housing that is affordable is being priced out,” said Michele Delisfort, Principal and Managing Partner, Nishuane Group LLC, noting, “Even with a college degree, it’s difficult to afford a home.” Josh Bauer, Staff Attorney at the Fair Share Housing Center declared, “Affordable housing is a racial justice issue.” Stephen Santola, Executive Vice President and General Counsel, at Woodmont Properties asked, “The entry-level cape is getting knocked down and replaced by a larger home selling for so much more—Where are the mid-level people going to live?”

Some solutions will come soon—next June—from the municipalities that must adopt new plans to build affordable housing under the Mount. Laurel doctrine. A new law enacted earlier this year, A4/S50, streamlines and clarifies the process; it assigned tasks to DCA, which Commissioner Suárez described:

- Issue non-binding affordable housing obligations for each municipality in October 2024.

- Gather and publish more robust municipal data on Affordable Housing Trust Funds and the number and type of affordable units that have been constructed.

- Develop criteria to streamline compliance and give municipalities more certainty.

She encouraged the audience to contact her office with concerns and suggestions.

Local officials face many challenges in siting affordable units. “How can communities plan and zone for affordable housing that advances smart growth while managing local opposition?,” asked moderator Chris Sturm, Policy Director for Land Use at New Jersey Future. Commissioner Suárez called for better communication. “People hate change, but elected officials need to have open conversations, and if they know the type of person who will live in affordable housing, it will help,” offering the example of a nurse who needs housing in the community where they provide healthcare. “Education is primary,” added Michele Delisfort, encouraging local leaders to explain redevelopment to stakeholders early and often and to get their feedback. She emphasized understanding the community, and compelling developers to deliver well-designed projects. Josh Bauers argued for a change in perceptions: “A four-story building will NOT detract from the property values of surrounding homes,” adding that people should view “multi-family” housing as “residential”. Steve Santola cited Princeton’s ordinance allowing Accessory Dwelling Units as a test case, which, if successful, could be a statewide remedy.

“People hate change, but elected officials need to have open conversations, and if they know the type of person who will live in affordable housing, it will help” –Department of Community Affairs Commissioner Suárez

All NJ municipalities urgently need practical tools to design and plan for housing. New housing should not only be affordable but climate resilient and in great neighborhoods where it’s easy to get around without a car and near parks and plazas. Panelists recommended:

- State support to increase local capacity for public outreach and early investment in comprehensive planning.

- Mandatory high-quality training for planning boards, in place of today’s lax program.

- Best practice tools, such as FAQs on planning and redevelopment, “Density by Design – NJ Style”, and templates for hosting effective planning board and governing body meetings.

- The ability to use more affordable housing trust fund monies for presentations and messaging, supported by revised DCA rules.

- Timely technical assistance that reaches towns early, before they begin their lengthy schedule of monthly meetings.

Affordable housing success stories like the Taylor Vose inclusionary housing project in South Orange can help local officials envision solutions for their community. See New Jersey Future’s Smart Growth Award winners for more.

Audience members raised broader affordability concerns, like the role consumer debt plays in limiting access to credit. Commissioner Suárez highlighted the difficulty municipalities face in hiring employees like emergency medical service staff and inspectors who do not earn enough to afford to live where they work. Panelists recommended holistic approaches to making New Jersey affordable—like using regionalization to lower the cost of local government (Suárez ), working with banks and financial institutions (Delisfort), and changing rental and mortgage requirements to focus on on-time rental payments (Rosario).

When asked, “What’s next for housing in 2050?” speakers shared visions that can inspire residents and local leaders today:

- More sustainable housing that relates to the environment, and communities that are better connected. -Michele Delisfort

- Look to student housing to see what’s next. -Stephen Santola

- Better public transportation. -Josh Baurs

- Open air spaces, plazas, and walkability, like those found in other parts of the world. -Peter Rosario

- Walkable, liveable places transformed from past industrial giants and malls. More community-centric places with multi-generational housing. -Commissioner Suárez

Chris Sturm closed the session by announcing that New Jersey Future and partners are launching a collaborative new initiative, Great Neighborhoods for All, which seeks to achieve visions like these because everyone in New Jersey deserves an affordable home in a community that’s a great place to live.

The Great Neighborhoods for All group is advancing three separate but interrelated initiatives:

- Building a statewide movement of local campaigns that advance inclusive, well-planned, and well-designed housing projects.

- Empowering local governments to solve pressing problems, such as addressing accelerating displacement of renters and meeting Mount Laurel Fourth Round deadlines with better planning for neighborhoods.

- Changing state policy in the next eighteen months.

To learn more, email Chris Sturm (csturm njfuture

njfuture org) or Alesha Vega (avega

org) or Alesha Vega (avega njfuture

njfuture org) .

org) .

Stormwater Pays No Mind to Municipal Borders—Why Should You?

July 30th, 2024 by Chris Sotiro

“Stormwater follows watershed boundaries, not political boundaries,” said Dr. Dan Van Abs, Professor at Rutgers University, during the 2024 New Jersey Planning & Redevelopment Conference (PRC). Many of New Jersey’s 564 municipalities grapple with flooding issues. For some, it is not uncommon for as little as three inches of rainfall to grind daily life to a halt. As average precipitation and severe weather events increase due to climate change, New Jersey will experience more frequent flooding. As the most densely populated and most developed state in the country, our flooding woes are amplified by the propensity for stormwater runoff to pollute sources of drinking water. In order to prevent chronic flooding and water quality impairments, municipalities must cooperate on a regional scale to improve their shared watersheds.

A panel of experts in the stormwater and watershed management spaces explored the benefits of a regional approach to watershed planning at the 2024 NJPRC, sponsored by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association. The session “Save Money, Talk to Your Neighbors: The Case for Regional Watershed-Based Planning” featured Dan Van Abs, Professor of Professional Practice at Rutgers University, Jim Cosgrove, President of One Water Consulting, Lindsey Sigmund, Program Manager at New Jersey Future, Mike Pisauro, Policy Director at The Watershed Institute, Nicole Miller, Principal of MnM Consulting, and Tom Dallessio, Executive Director of the Musconetcong Watershed Association.

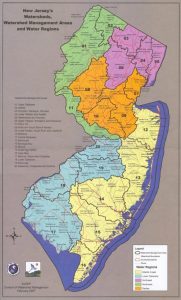

As Mike Pisauro of The Watershed Institute explained, a major component of the new Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permits—applicable to every municipality across the state—is the development of a Watershed Improvement Plan (WIP). While it is important to identify avenues for reducing water quality impairments, municipalities are limited in their ability to holistically address the watershed they occupy. Whereas a municipality can be affected by poor watershed management upstream, it cannot enforce improvement projects outside of its own local borders.

New Jersey’s Watershed Management Areas (WMAs)

Some municipalities have simply been dealt a bad hand of cards, like Manville Borough, which sits at the bottom of the North and South Branch of the Raritan River. During Hurricane Ida ten inches of rain over a three-hour period led to a record-high 27.66-foot crest of the Raritan River, leaving some residents to experience flood waters reaching the second floor of their homes. “Manville can do the greatest job in the world with its Watershed Improvement Plan, but if they don’t incorporate what is going on upstream, there is no way they will solve flooding,” according to James Cosgrove of One Water Consulting. It is an unfortunate reality that the inaction of upstream communities often sets the stage for water quality impairments that are felt by downstream residents. Absent strong regional cooperation between municipalities throughout the entirety of the North and South Branch Raritan Watershed Management Area to take measures to capture and store excess stormwater, Manville will be on its own.

President Joe Biden tours a neighborhood in Manville Borough and talks with residents affected by the flooding caused by Hurricane Ida

Operating as 564 separate systems is both tedious and redundant when it comes to watershed planning. While some municipalities may not deal with severe flooding as frequently as others, all towns, and the state, benefit from a healthy watershed. Simple river restoration actions, like tree plantings, streambank support, and water quality testing can ensure that freshwater drinking water sources are protected from non-point source pollutants. Low-cost green infrastructure projects capture, store, and filter excess stormwater to prevent it from overwhelming roads and waterways.

The Watershed Improvement Plan (WIP) for each municipality entails three phases: a Watershed Inventory Report, a Watershed Assessment Report, and a final WIP Report. While each municipality must complete its own WIP, there are opportunities for collaboration throughout its multi-year development process. For example, municipalities can work together to complete outfall drainage area mapping, which often spans across local borders and may require assistance from external consultants. Also, holding public information sessions to relay findings from Watershed Assessment Reports would be incredibly more efficient if convened on a regional basis, in contrast to independent meetings with residents. An open dialogue is vital to the watershed improvement planning process. “We want to engage community representatives early in the process. Across the state, advocates are working on these exact kinds of solutions, and they may have the solutions already in play, but simply need to be connected with one another to create effective change,” according to Nicole Miller of MnM Consulting.

Regional collaboration has the capacity to effectively and efficiently improve flooding and water quality, foster relationships between municipalities, save time, and save costs for all parties involved. Local watershed associations are well-poised to facilitate regional conversations, as they are well-established groups that routinely work with municipal officials. Municipalities may lack the tools or expertise for regional watershed-based planning on their own, but as Tom Dallessio of the Musconetcong Watershed Association explains, “Our job as a watershed association is to work with communities to improve water quality… You can’t address issues like water quality without a plan in place.” As municipalities work to draft their Watershed Improvement Plans under the new MS4 Permits, they must pursue every opportunity to work across municipal borders and with local watershed organizations to pool resources and share knowledge to build a more resilient watershed in the face of exacerbated flooding and water quality impairments under climate change.

New Jersey’s Housing Landscape: The Mount Laurel Doctrine and the Search for the Missing Middle

July 30th, 2024 by Tim Evans

The rising costs of housing in New Jersey are affecting everyone, especially individuals and households at the lower end of the income spectrum. New Jersey’s unique Mount Laurel doctrine is meant to address the need for housing for lower-income households, but it also indirectly has a major effect on the supply of market-rate multi-family units in the process. The process by which towns satisfy their affordable housing obligations does not guarantee a full range of housing options for a full range of household types and incomes. The Mount Laurel requirements ought to serve as a prompt for towns to think holistically about their housing supply in general—how much and what types of housing will they need to accommodate the needs of future residents?

Panelists in the session “Knowing the Numbers: Housing Allocation, Patterns of Development and the Future of Housing” at the 2024 Planning and Redevelopment Conference discussed the current state of affairs in housing in New Jersey, for affordable housing and beyond. Moderator Creigh Rahenkamp, Principal of CRA, LLC, and Tim Evans, Research Director at New Jersey Future, gave background about the housing supply in general, and Katherine Payne, Director of Land Use, Fair Share Housing Center; Graham Petto, Principal, Topology; and David Kinsey, Partner, Kinsey & Hand talked about what to expect from the latest changes to the state’s system of incentivizing affordable housing. Panelists all agreed that the Mount Laurel system is necessary but not sufficient to provide the full range of housing options that New Jersey’s future population will need.

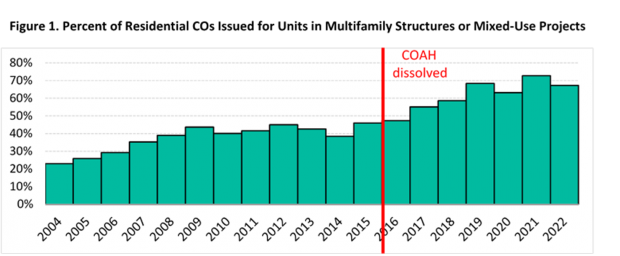

“Mount Laurel” and Affordable Housing

The Mount Laurel doctrine refers to a series of New Jersey Supreme Court decisions that direct municipalities to provide their “fair share” of the regional need for low- and moderate-income housing. For many years, enforcement of the requirements was the responsibility of the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH), but the Council was effectively dissolved in 2015 when the Court deemed it ineffective and handed enforcement authority back to the judicial system. Payne cited her organization’s 2023 report Dismantling Exclusionary Zoning: New Jersey’s Blueprint for Overcoming Segregation to point out that the annual production of affordable units increased substantially after 2015 under the subsequent more rigorous court oversight. (She pointed out that the vast majority of affordable housing is produced in the form of multifamily housing.) The report also found that most of the overall growth in multifamily housing (primarily apartments) over the same time period has been achieved in inclusionary Mount Laurel projects, projects that contain both income-restricted and market-rate units, to the extent that 81% of all multifamily units built since 2015 were built in connection with the Mount Laurel process. Reinforcing this relationship, Evans cited data showing certificates of occupancy (COs) for multifamily housing rising in the post-COAH era (see Figure 1 ) to the point where multifamily units now account for more than half of all housing production. “This shift in permitting activity is being driven by Mount Laurel-associated re-zonings,” Payne said.

Production of multifamily housing has increased steadily in the post-COAH era. More than 4 out of 5 multifamily units built since 2015 are associated with Mount Laurel projects, either as affordable units or as market-rate units that are part of mixed-income projects.

Administration of the Mount Laurel process has recently undergone another significant change with the passage of new legislation, in the form of Assembly Bill 4/Senate Bill 50 this year. Among other things, the legislation sets up an oversight mechanism within the executive branch and directs the Department of Community Affairs to implement a methodology for determining municipal affordable housing obligations, based on three factors—income capacity, non-residential property valuation, and developable land. While the rules will take time to create, Petto said municipalities can and should get started now in preparing plans for compliance, including thinking about where in town the Mount Laurel units will be located and how to earn extra credit for certain types and locations. Kinsey mentioned that the legislation allows for bonus credits for such features as proximity to public transportation, special-needs or supportive housing, and redevelopment of a retail, office, or commercial site.

Redevelopment as the New Paradigm

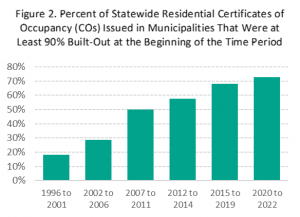

Many new Mount Laurel units will be constructed in redevelopment areas, if the overall pattern of population growth in recent years is any indication. Evans showed that most of the state’s housing growth over the last decade and a half has been happening in already-built-out areas (see Figure 2 ).

Redevelopment is the new normal: An increasing share of New Jersey’s housing growth has been happening in already-built places.

It is clear that “built-out” does not necessarily mean “full,” and that redevelopment areas offer plenty of opportunities for municipalities to create more housing, both for Mount Laurel and market-rate. As such, the new legislation requires municipalities to develop plans for “conversion or redevelopment of unused or underutilized property, including existing structures if necessary, to assure the achievement of the municipality’s fair share” of affordable housing.

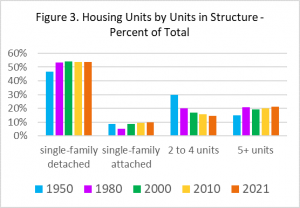

The “Missing Middle” Is Still Missing

Payne reminded listeners that the Mount Laurel doctrine originally arose when the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that municipalities cannot practice “exclusionary zoning,” by which they effectively exclude lower-income households by writing their zoning codes to allow nothing but single-family detached homes, which are less affordable to households of modest means. Such zoning is still very common: “About 75% of land in major US cities is zoned exclusively for single-family housing, which has implications for access to opportunity,” Payne said.

While the Mount Laurel process was set up to ensure the provision of housing for lower-income households, it does not address other types of housing that are left out by exclusionary zoning and are thus in short supply. The wide array of housing options between single-family detached units on one end of the scale and large apartment buildings on the other are often called the “missing middle,” because many places simply don’t plan for them. This includes options like duplexes, triplexes, small apartment buildings, apartments above stores, and accessory dwelling units (ADUs), a category that itself includes small, separate units that are attached to or on the same property as a larger unit, like above-garage apartments or “in-law suites.” Evans illustrated how housing units in 2-, 3-, and 4-unit buildings have declined as a share of total housing units, from 30% of all units in 1950 to half that share as of 2021 (see Figure 3 ). Kinsey further noted that the number of units in structures with 2 to 4 units has actually decreased in absolute terms, dropping from about 514,000 in 1970 to about 490,000 in 2020.

“Missing middle” housing options in buildings with 2 to 4 units have declined dramatically since 1950 as a share of total housing units.

Another conference session, “We’re Missing Middle Housing in New Jersey: How to Fix It,” was devoted entirely to these missing options and strategies to bring them back. One of the speakers in that session, Karla Georges of the national American Planning Association, identified states where “missing middle” housing bills have passed, including Washington, Colorado (HB1316 and HB1175, and Arizona. Kinsey mentioned one modest New Jersey effort, bill S2347 currently being considered by the legislature, that would authorize ADUs statewide. Meanwhile, some New Jersey municipalities have legalized ADUs on their own, without waiting for statewide legislation.

In any event, while New Jersey is ahead of most of the rest of the country in having the Mount Laurel doctrine and its supporting legislation, this is insufficient as a mechanism for ensuring the production of a full range of housing types, without which people will continue to migrate out of New Jersey in search of cheaper options. As New Urbanist pioneer Peter Calthorpe has observed at the national level, “We cannot build this country on subsidized housing. We’re never going to get the end result. We have to create the context, the policies, and the zoning that make middle housing viable and located in the right locations.” New Jersey now needs to follow the lead of other states in exploring strategies to break the stranglehold of single-family zoning, so that households of all incomes can afford to call New Jersey home.

Municipal Leaders Claim Public Engagement is Largest Asset to Lead Replacement Efforts

June 24th, 2024 by New Jersey Future staff

By Andrea Jovie Sapal and Deandrah Cameron

“We collectively work towards a future where every resident in New Jersey has access to clean, safe, and lead-free drinking water by fostering collaboration and sharing knowledge through innovation,” declared Richard Calbi, Director of Ridgewood Water, as he opened the lead service line replacement session at the 2024 Planning and Redevelopment Conference. This session focused on a critical environmental justice issue that demands our urgent attention—the presence of lead in drinking water in New Jersey.

Lead service lines (LSLs) account for 75% of all lead in drinking water exposure and are particularly harmful to formula-fed infants and children under six. New Jersey leads the way in LSL replacement with one of the strongest mandates across the country. In 2023 NJ was designated by the Biden Administration as one of four states participating in the US Environmental Protection Agency’s LSL Replacement Accelerator program, in part for NJ’s aggressive approach to service line replacement and emphasis on planning and municipal coordination. Last month, the EPA announced that NJ will receive $123 million in federal funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law through the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund. The cost estimate for LSL replacement in NJ is roughly $3 billion.

Although funding is a major issue, engaging customers proves to be the most difficult hurdle. Moderator Richard Calbi stated, “The bulk of the financial burden will fall on water systems, resulting in increased water rates for consumers.” Consumers, i.e. regular households and businesses that pay for water, are the biggest stakeholders and face the burden of paying for their lead lines as water systems design replacement programs. While some programs offer free replacement, most systems will charge a cost. According to one report, a single LSL replacement could cost on average $6000 with high costs over $9,000—accounting for the cost of living differences, unique building or pavement materials, paving requirements, and unique permit fees. Speakers Kouao-eric Ekoue, Superintendent, City of New Brunswick Water Utility; Noemi de la Puente, Principal Engineer, Trenton Water Works; and Stephen Marks, Town Administrator, Town of Kearny shared their expertise on the state and federal partnerships, cost reduction strategies, and community engagement at the “Leading the Way: Cost-Saving Solutions for Coordinating Lead Service Line Replacement with Municipal Projects and Processes” session.

Featured speakers Kouao-eric Ekoue of New Brunswick Water Utility and Noemi de la Puente of Trenton Water Works (TWW) represent two of NJ’s accelerator cities (more below). State support for local assistance is critical for advancing LSL replacement projects. In conjunction with the federal LSL Replacement Accelerator program, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) launched NJ-TAP, an initiative providing enhanced technical assistance for disadvantaged communities to provide safe and reliable drinking water to residents. New Brunswick Water Utility leverages both federal and state programs to assist in changing ordinances, accessing funds through the SRF program and bonds, integrating data validation tools, and self-testing and electronic identification surveys as part of community outreach. On the topic of effective strategies to gain community support, Ekoue stated that his administration is fully involved in the process, emphasizing the importance of municipal engagement early on since without that buy-in, the projects are not going to go anywhere fast.

New Jersey’s ten federal LSL Replacement Accelerator cities include:

- Blackwood

- Camden

- Clementon

- East Newark

- Harrison

- Keansburg

- Keyport

- New Brunswick

- Trenton

- Ventnor City

LSL replacement can be challenging for water systems that serve multiple municipalities where program planning looks different for each locality. This type of coordination and cross-collaboration requires ingenuity; moderator Rich Calbi noted, ”We must explore innovative strategies and best practices to help municipalities navigate these challenges effectively and alleviate the burdens placed on residents as we work toward compliance with this vital mandate”. The City of Trenton serves five municipalities: Trenton, Ewing, Hamilton, Lawrence, and Hopewell, each requiring a unique approach.

Trenton Water Works’ engineer Noemi de la Puente discussed challenges and potential solutions around the Three Ps: Paving, Policing, and Permitting. Each municipality has different paving jurisdictions, and without coordination, replacements could be unnecessarily costly. In 2022, when de la Puente inherited the program from her predecessor, she asked, “How are we going to reshape the TWW LSL replacement program overall at a rate that isn’t expensive?”. Some potential cost-saving solutions de la Puente is looking to explore include streamlining the hyperlocal permitting process by coordinating LSL replacement plans with paving projects associated with sewer maintenance plans, main replacements, and other paving projects across jurisdictions. Since funding is a challenge, de la Puenta emphasizes that partnering with these projects would allow the leverage of Clean Water State Revolving and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds as well as funds allocated through the NJ-Moves program for paving projects. To date, de la Puente mentions needing a total of 961 permits totaling $111,476, concluding that these fees could be significantly lower with coordinating across programs.

De la Puente stressed that the strongest collaboration TWW can form is with their customers because they require access to 62,000 basements to identify lead service lines. The faster they can identify the inventory, the quicker they can complete the project. “If I [knew] my entire inventory next week, the rest of my lead service line replacement project will go much more smoothly,” concluded de la Puente.

If I [knew] my entire inventory next week, the rest of my lead service line replacement project will go much more smoothly.

—Noemi de la Puente of Trenton Water Works

The Town of Kearny also utilized an ordinance to develop a free and mandatory program coupled with a cost reduction that includes combining the town’s resurfacing program with its LSL replacement program. However, Marks expressed that it won’t happen all at once “Given the density of digging test pits every 25 to 40 or 50 feet, it made the most sense for the town of Kearny to incorporate the lead service line replacement into the road resurfacing program. The town has a moratorium on digging up any streets that have been paved within the last five years, so we’re actually focused on all the streets that haven’t been paved on the outer end of 10 to 15 years or more.” This means depending on when the road was last paved, customers may have to wait years before the replacements are scheduled to begin. To mitigate this, the Mayor and Council also passed supplementary ordinances to reimburse all customers who coordinate their own replacement should they decide to move ahead of the town’s schedule.

“100% of the census tract for the Town of Kearny is considered overburdened by the state of New Jersey,” and about half (46%) of the town is considered low-moderate income

—Stephen Marks, Town of Kearny

Overburdened communities often struggle to pay cost shares. Town of Kearny Administrator Stephen Marks highlighted that “100% of the census tract for the Town of Kearny is considered overburdened by the state of New Jersey,” and about half (46%) of the town is considered low-moderate income. The Town of Kearny also utilized funding through the Federal Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) as an alternative source of funding through which a portion of the town became eligible based on census tract and income level. Marks explained that funding is a constant challenge and that municipalities are constantly deciding between the lengthy SRF process that may offer the potential for principal forgiveness or choosing to engage in the private market which could be more costly but quicker. In response to the notice of the $123 million in federal funding, Marks stated that municipalities have a decision to make as regards timeliness and meeting the 2031 goal. For example, he explained that an $8 million project is a trade-off between a “six-month” I-Bank application process with the hope of possible principal forgiveness compared to self-financing through the private market where there is no principal forgiveness but saves time. In addition to funding and coordination Marks also shared similar challenges to his fellow panelists around property access, expressing that residents typically do not want the town accessing basements or private spaces especially where they potentially have an unpermitted conversion of the basements.

The overlapping theme among the municipal leaders was that community engagement is extremely important, especially in overburdened communities where customers face a number of challenges, including cost sharing for LSL replacement. Partnerships with community groups and local leaders play a pivotal role in the successful replacement of LSLs and facilitating coordination between different jurisdictions and projects. The ultimate objective of achieving lead-free drinking water necessitates a multi sector approach that offers cost-effective solutions. Cooperation among various local, regional, and state leaders is crucial for effective implementation. The Primer for Mayors outlines ten efficient measures for LSL replacement and guides municipal officials on how to initiate this process in their community. This Jersey Water Works resource is a prime example of an initiative that supports all municipalities by providing the necessary tools and strategies for effectively replacing lead service lines. By July 10, 2024, water systems must submit their updated annual inventories and LSL progress reports. This increased transparency and communication are crucial steps towards addressing the ongoing issue of lead in drinking water.

To learn more about Jersey Water Works and the Lead in Drinking Water Taskforce, join us at the July 17th membership meeting in person. Registration is free, attendees do not need to be a member of the collaborative to attend. Register today! For more information contact Jersey Water Works (info jerseywaterworks

jerseywaterworks org) .

org) .

Unlocking Opportunities: Securing Funding for Trail-Related Projects

June 24th, 2024 by Zeke Weston

As the nation’s most densely populated state, New Jersey packs in more people per square mile than anywhere else. Our most vibrant cities and towns include compact, walkable downtowns and active streetscapes—complemented by accessible greenways and trails for recreation, a respite from urban life, and healthy, carbon-free travel. But being the Garden State, we can do so much more.

New Jerseyans enthusiastically support and want more greenways and trails. The public input process for the new draft Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) included over 15,000 survey responses that identified hiking, walking, and gathering as top priorities, with trails highlighted as one of the most important outdoor amenities. Nonetheless, residents from the SCORP’s public focus groups mentioned several barriers to full participation in outdoor recreation, notably limited transportation options, whereby participants can comfortably travel to outdoor spaces. To overcome these barriers, towns and counties need to comprehensively plan and design trail projects that are safe, accessible, and well-connected. Most communities want to build outdoor recreation and active transportation facilities but lack the funding and resources to make them a reality.

Most communities want to build outdoor recreation and active transportation facilities but lack the funding and resources to make them a reality.

A panel titled “Connecting Communities to Capital for Greenways, Trails, and Bike Paths” addressed these issues and priorities at the 2024 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference (NJPRC), sponsored by New Jersey Future and the New Jersey chapter of the American Planning Association. Panelists brought a broad range of experiences to the discussion and an even greater depth of on-the-ground experience. They included: moderator Olivia Glenn, Chief of Staff and Senior Advisor for Equity, US EPA Region 2; Byron Nicholas, Chief, Division of Planning, Hudson County; Elizabeth Dragon, Assistant Commissioner, Community Investment and Economic Revitalization, NJ Department of Environmental Protection; Laine Rankin, Assistant Commissioner, Local Resources and Community Development, NJ Department of Transportation; and Teri Jover, Borough Administrator and Economic Development Director, Borough of Highland Park.

In her opening remarks, Olivia Glenn emphasized the importance of federal funding for state and local governments to invest in active transportation infrastructure, especially from the Inflation Reduction Act. She highlighted the $4 million awarded to New Jersey’s local, county, and state governments from the EPA’s Government to Government program last year. The funds will be used for government activities in partnership with Community-Based Organizations that result in measurable environmental and public health improvements in overburdened communities. One of the many types of projects the program can fund is urban greenways. Urban greenways provide access to nature and clean transportation corridors while simultaneously reducing the urban heat island effect. Because of their multifaceted benefits, Glenn emphasized the ability for trail-related projects, like urban greenways, to be funded by a wide variety of grant programs, not just transportation ones.

Teri Jover provided insight into how these types of projects come to fruition at the local level in a municipality. The Highland Park River Greenway was a dream of the Borough’s residents and elected officials for decades. In 2017, the Borough finally developed a one-page description of the Greenway to share with the county and state. At that time, Jover noted that the project needed to be fleshed out in more detail for it to advance. Because of Highland Park’s limited staff capacity and resources, she highlighted the Borough’s inability to afford a consultant despite needing one. Fortunately, Highland Park applied for and received a budgetary grant from the NJ Department of Community Affairs to conduct the feasibility studies and topographic surveys needed for the project, which was funded by a one-time earmark from the state legislature. This grant allowed the Borough to conduct the analysis and planning to push the project forward, but Jover acknowledged the need for additional money to construct and then maintain the Greenway. This will be a long-term project, as many greenways are, and, she emphasized the importance of staying committed to these projects until the end.

Byron Nicholas spoke to the regional perspective and process for advancing trail projects, drawing on his experience with various Greenways in Hudson County. Because Hudson County is the most densely populated county in the state, access to riverfronts and open spaces is limited despite the existence of the Hudson, Hackensack, and Passaic Rivers. Therefore, the county looked at how to improve access to outdoor amenities while providing alternate transportation options. This resulted in the 2022 Hackensack River Greenway plan. The County needed to develop a concept design for the Lincoln Park segment of the Hackensack River Greenway, so they applied for and received a grant of approximately $1.5 million from the Transportation Alternative Program (TAP). The TAP grant funded the preliminary and final designs of the Greenway and the beginning of construction. From this experience, Nicholas emphasized the importance of establishing and maintaining relationships with your project partners. He noted that their bi-monthly working group meetings were critical to the project’s success and should be a component of all regional trail projects.

Hackensack River Greenway

Elizabeth Dragon emphasized the importance of intentional planning for successful trail projects. Effective trail planning includes research, community engagement, and alignment with state and local initiatives. When reviewing grant applications to the Green Acres Program, Dragon noted that the most competitive applications identify the project’s economic, environmental, and community benefits and demonstrate its positive impact on local business, tourism, environmental preservation, and social cohesion. She highlighted the importance of addressing the NJ Department of Environmental Protection’s triple bottom line in the grant application: economy, environment, and people. Connecting your trail or greenway project to these priorities and outcomes cannot be overstated. Similarly, Dragon noted the need to identify how the project complements local and state land use plans. The most successful applications are consistent with these plans and their priorities.

The most competitive grant applications highlight the project’s economic, environmental, and community benefits and identify its positive impact on local business, tourism, environmental preservation, and social cohesion.

Laine Rankin described the funding opportunities available at the NJ Department of Transportation for trail-related projects. She identified the state’s Bikeways Program and Municipal Aid Program as opportunities for towns and counties to access funding for such projects. Rankin made sure to note that the state’s programs are intended for shovel-ready projects that have already completed the planning and design phases. For example, Montgomery Township received a $360,000 Municipal Aid grant in 2020 to build 1.5 miles of bike lanes and 2.1 miles of new multi-use paths around Skillman Park. On the other hand, Federal programs for trail-related projects, like the Transportation Alternative Set-Aside (TASA), do not have the same shovel-ready requirements. For instance, Burlington County received a $440,000 TASA grant in 2020 to build a portion of the Delaware River Heritage Trail along the Route 130 bypass. Rankin reiterated the importance of knowing what project types each program funds so that towns apply to the most appropriate program for their needs.

Now, more than ever, New Jersey needs to meet its residents’ wants and needs for greenways and trails that provide equitable mobility and access to nature. The state’s municipalities and counties can make this a reality, but they need to know the appropriate funding programs to do so. Towns interested in trail-related projects should contact their County planning departments and Metropolitan Planning Organizations for further assistance and information.