New Jersey Future Blog

Job Growth Finally Following Population to Compact Centers

May 3rd, 2019 by Tim Evans

-

Aerial view of Newark, which has seen the largest improvement in private-sector job numbers since 2014.

Population growth began returning to compact, walkable places starting around 2008

- Job growth, in contrast, did not appear to be following suit – the 2008-2014 period still looked a lot like 1999-2008

- From 2014 to 2017, though, jobs appear to be belatedly following people (especially Millennials) back into cities and older suburban downtowns

Population growth began returning to compact, walkable centers back in the mid-to-late 2000s, as the Millennial generation began aging into young adulthood and expressing their preference for walkable urbanism. But a similar trend had not manifested itself in the geographic distribution of job growth – until now.

New Jersey Future noted the shift in population as early as 2009 (“Suburbs Still Growing … But So Are The Cities”; “Cities Show Signs of Reversing Trend, Gaining Population”), with older, built-out places where populations had long been stagnant or declining suddenly seeing their first population growth in several decades. The Great Recession of 2008 seemed like the most obvious cause at the time, although it has since become clear that the movement back into cities and older suburbs with traditional downtowns is part of a longer-term trend. (For a more thorough summary of this trend, see “Are the Suburbs Back? Depends On How You Define ‘Suburb’.”)

We have documented this trend by tabulating population growth in groups of municipalities based on how well the municipalities perform on three “smart growth” metrics (first introduced in the 2014 report Creating Places to Age in New Jersey): net activity density (population plus jobs per square mile), presence of a mixed-use “center,” and local street network density (a measure of connectivity and walkability). Based on the most recent (2017) Census Bureau municipal population estimates, our analysis indicates that the 124 municipalities that score well on all three metrics accounted for 61.5 percent of statewide population growth from 2008 to 2017, after having accounted for only 6.1 percent of growth from 2000 to 2008. In contrast, municipalities not scoring well on any of the metrics saw their share of growth decline from 38.8 percent for the 2000-2008 period to just 11.9 percent for 2008-2017. This pattern has held consistently since we first started tracking it in 2009.

Employment growth, on the other hand, had not been following a similar pattern. Fortune magazine noted the first stirrings of a shift in employment in 2011 (“In a bid to attract younger employees, more companies are moving out of the ‘burbs and back into cities”), but as of 2014 the trend was not yet discernible in New Jersey employment data.

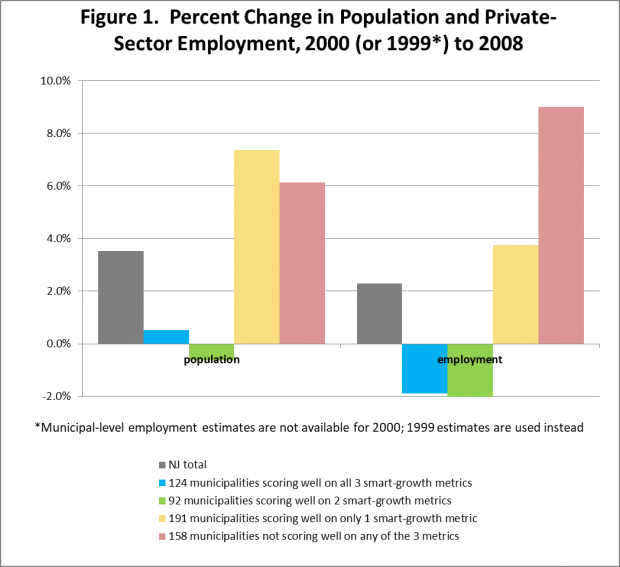

According to the New Jersey Department of Labor, from 1999 to 2008 (the year that seemed to mark a turning point in the distribution of population growth), the state gained a total of 74,672 private-sector jobs. Consistent with what had been happening in prior decades, and consistent with trends in population growth at the time, the municipalities that score well on all three smart-growth metrics lost 20,891 private-sector jobs over this period as a group (see Figure 1). And 57 of them individually lost jobs, so it was not simply a matter of one or two large, declining cities dominating the job-change picture; the losses were broad-based. Meanwhile, the 158 municipalities that do not score well on any of the three metrics collectively gained 55,544 private-sector jobs.

From 2000 to 2008, as in the previous two decades, population growth and employment growth were both still largely happening in car-oriented suburbs, with the state’s cities and older suburban downtowns either stagnant or declining.

Of the biggest gainers – the 20 municipalities that gained at least 3,000 private-sector jobs over the nine-year period – only Jersey City, Hoboken, and Pennington score well on all three metrics, and another three – Neptune Township, Summit, and Brick – score well on two of them. Meanwhile, the other 14 are mostly suburban, highway-oriented employment centers, with seven – Parsippany-Troy Hills, Bridgewater, Cherry Hill, Lakewood, Toms River, Moorestown, and Robbinsville – scoring well on only one of the metrics, and the other seven – Morris Township, Evesham Township, Monroe Township (Middlesex County), North Brunswick, Franklin Lakes, Hillsborough Township, and Mount Laurel – not scoring well on any of them. (The picture is similar if we expand the analysis to the 34 municipalities that gained 2,000 or more private-sector jobs: 15 of them – almost half – scored well on none of the metrics, and another 11 scored well on only one of them, while only four scored well on two metrics and another four scored well on all three.)

Like population growth at the time, employment growth through most of the 2000s was still mainly happening in car-oriented suburbs, with Jersey City and Hoboken standing out as the exceptions that perhaps offered an early hint of the change to come.

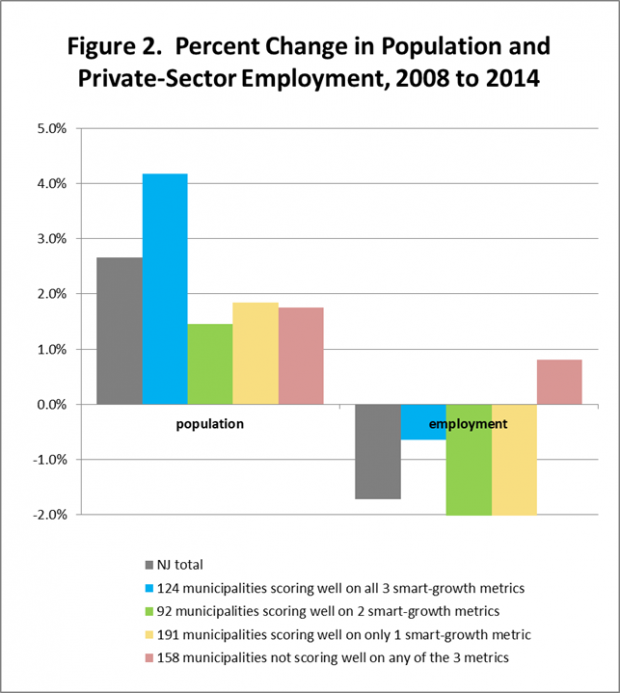

From 2008 to 2014, in the wake of the Great Recession, the locus of population growth changed dramatically, while job growth largely continued to follow the suburban model. The state lost 57,210 private-sector jobs over this period, with the municipalities that score well on all three smart-growth metrics collectively losing 7,073 of those jobs, while the lowest-scoring municipalities actually added 5,423. The heaviest private-sector job losses over the period were sustained by the two intermediate groups, the municipalities that score well on either one or two of the metrics (see Figure 2).

Between 2008 and 2014, in the wake of the Great Recession, New Jersey’s cities, towns, and older, walkable suburbs suddenly began accounting for the bulk of statewide population growth, but job growth did not follow suit. The state as a whole shed more than 50,000 private-sector jobs over this period, but the most car-dependent suburban municipalities as a group still managed to post small job gains.

Lower-scoring municipalities continued to dominate the list of the top job-gaining municipalities between 2008 and 2014. Thirty-six municipalities gained at least 1,000 private-sector jobs over the six-year period, of which 15 do not score well on any of the three smart-growth metrics and another eight score well on only one. Meanwhile, 11 of the 36 score well on all three of the metrics and another two score well on two of them. While only about a third of the biggest gainers over this period scored well on two or three of the metrics, the high-scoring municipalities’ larger share of the group (as compared to 1999-2008) may have been a prelude to the bigger change to come.

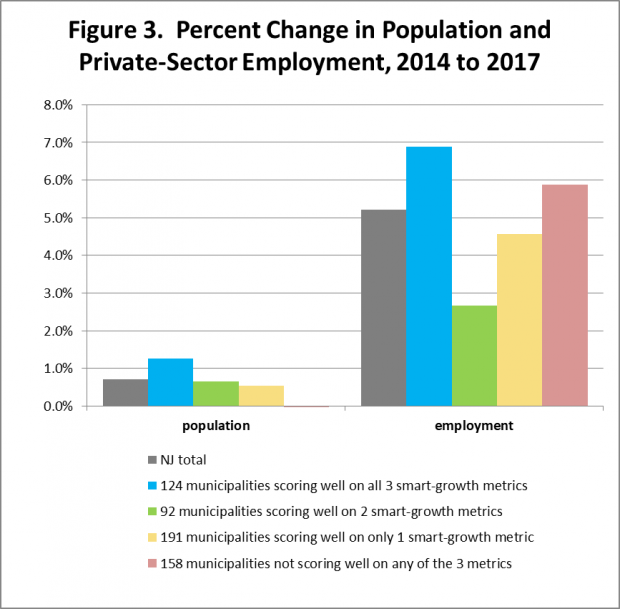

From 2014 to 2017, the job-change picture has come to resemble more closely the population-change picture (see Figure 3). Population growth was relatively slow during this period but remained dominated by older, walkable, mixed-use centers. In fact, the most car-dependent group of municipalities collectively exhibited zero population change. Meanwhile, the state added 169,939 private-sector jobs, a 5.2 percent increase over 2014, as it finally emerged from the shadow of the Great Recession. Of these, 74,287 – 44 percent of the total – were added by the municipalities that score well on all three of the smart-growth metrics, representing a 6.9 increase for that group. The lowest-scoring municipalities added only about half as many new private-sector jobs – 39,907, or about 23 percent of the total, although this still represented a 5.9 percent increase for this group, due to the smaller size of the initial job base.

Since 2014, New Jersey’s cities, towns, and older, walkable suburbs are now accounting for a plurality of the state’s private-sector job growth, similar to the way they have dominated population growth since 2008.

Among the 51 municipalities adding 1,000 or more private-sector jobs over this period, the number that scored well on all three smart-growth metrics (19) actually outnumbered those not scoring well on any (15), with 13 municipalities scoring well on only one metric and four scoring well on two. During this latest period, municipalities scoring well on two or all three metrics thus accounted for almost half of the biggest gainers, up from a little more than a third between 2008 and 2014. And among the biggest of the big gainers – the 13 municipalities that added at least 3,000 private-sector jobs, half of them – Jersey City, Newark, Carteret, Hoboken, Morristown, Swedesboro, and Camden – scored well on all three metrics. Only one of these 13 – Evesham Township – didn’t score well on any of the metrics. Mixed-use, walkable, transit-friendly “centers” are now showing signs of dominating the state’s job growth the same way they have been dominating its population growth since 2008.

Why the lag time? That is, why did cities and older, walkable suburbs start capturing the lion’s share of population growth so long before a similar pattern started showing up in the job-growth data? Part of the explanation may simply be that it is a longer and more involved process to relocate a company than to move a household, so perhaps some lag time is to be expected. This would explain the delay, but would not necessarily explain why, when companies do move, they are choosing to relocate to the same sorts of places that have been attracting young workers.

Instead, what we may be witnessing is a change in the employer/employee dynamic, in terms of how companies make their locational decisions. At New Jersey Future’s recent Redevelopment Forum, Eugene Diaz, the founder and principal of real estate development and financing firm Prism Capital Partners, commented during the morning plenary panel that 10 years ago, the corporate officer they dealt with when a company was seeking advice on where to locate in New Jersey was usually the chief financial officer; today, it’s the head of human resources. Under the old model, a company decided where to locate based on market, cost-per-employee, and taxation considerations, and employees were expected to follow. Now, younger workers are moving to their preferred living locations first, and companies find themselves having to follow their prospective recruits into the live-work-play-shop environments where they want to live.

Morris Township surrounds Morristown so it benefits from its downtown vibe!